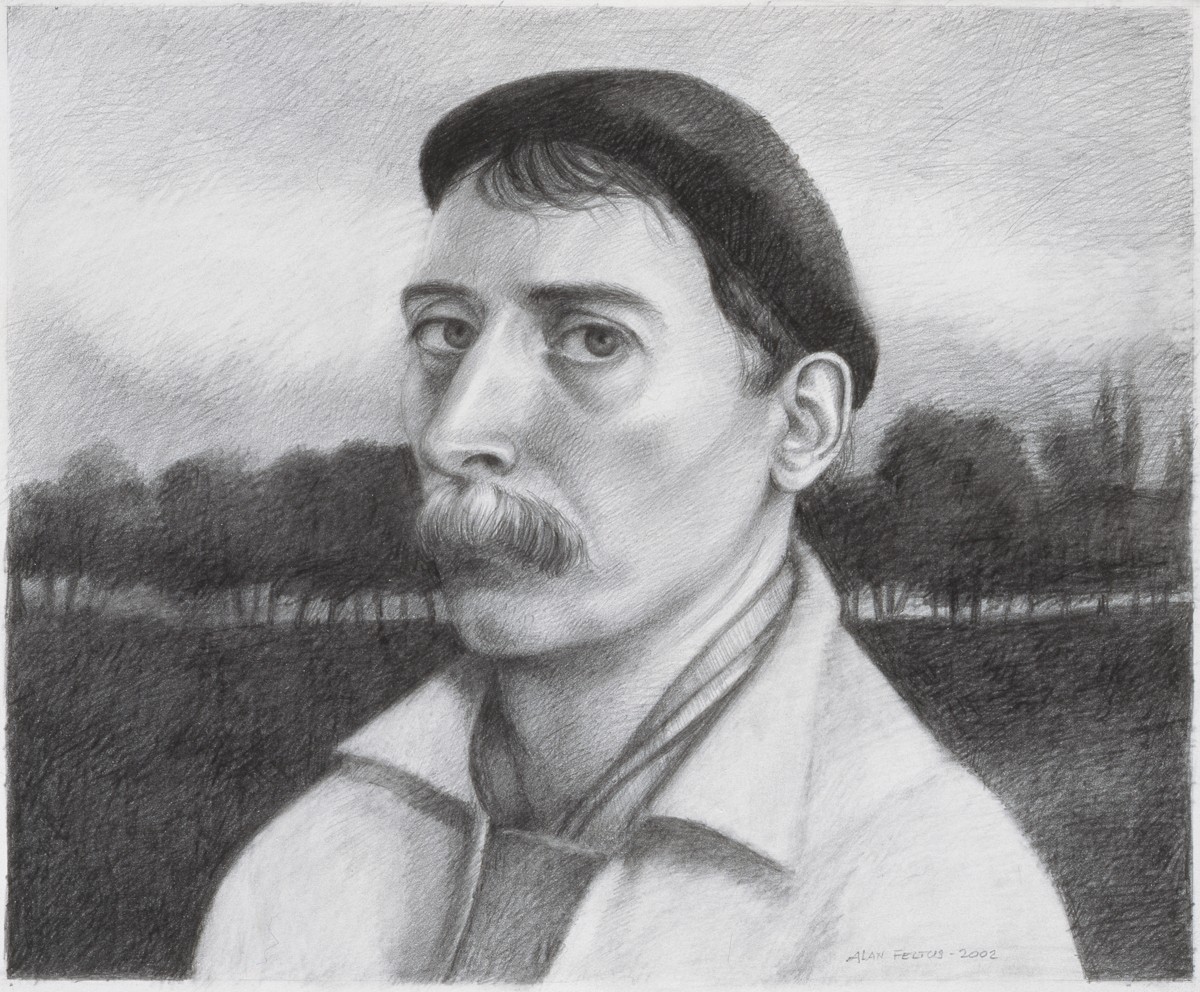

Self-Portrait (Trees Across Horizon), 2002

graphite on paper, 12 ½ x 15 ⅝ inches (32 x 40 cm)

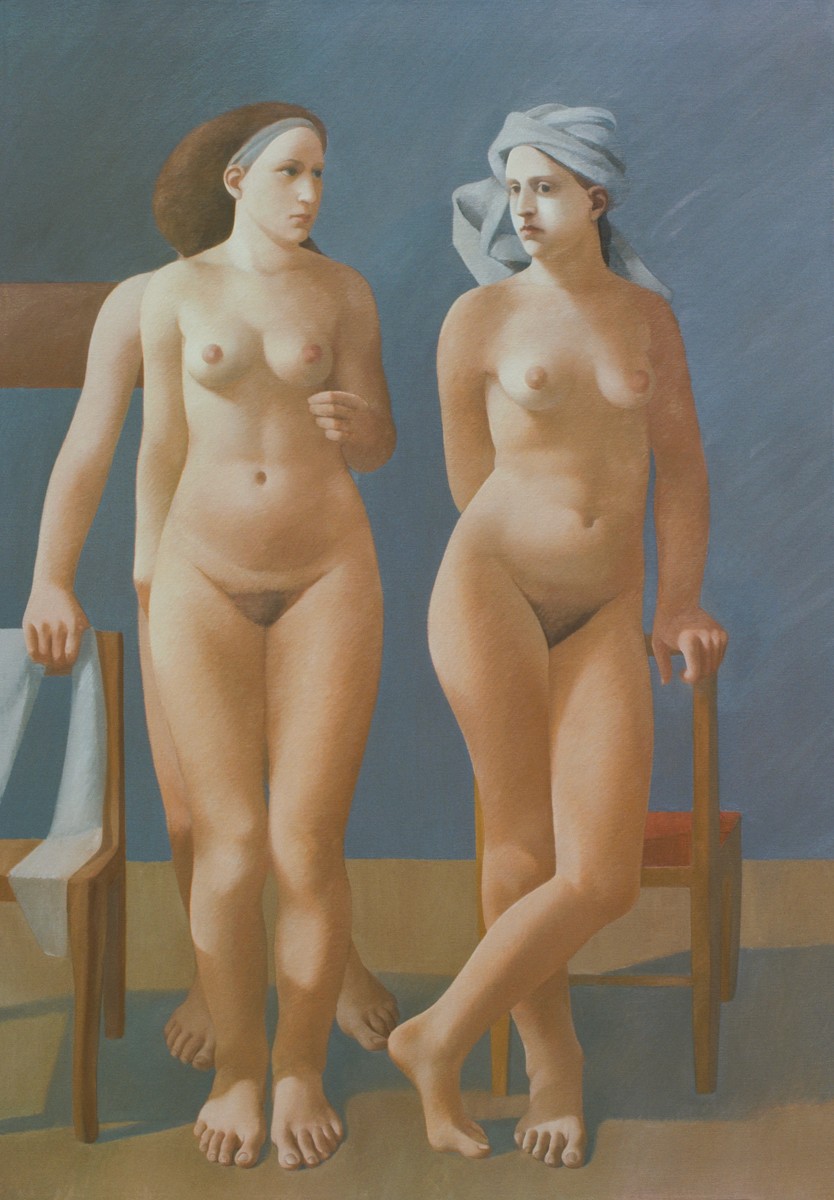

Two and a Half, 1974

oil on linen, 61 ½ x 43 inches (156 x 109 cm)

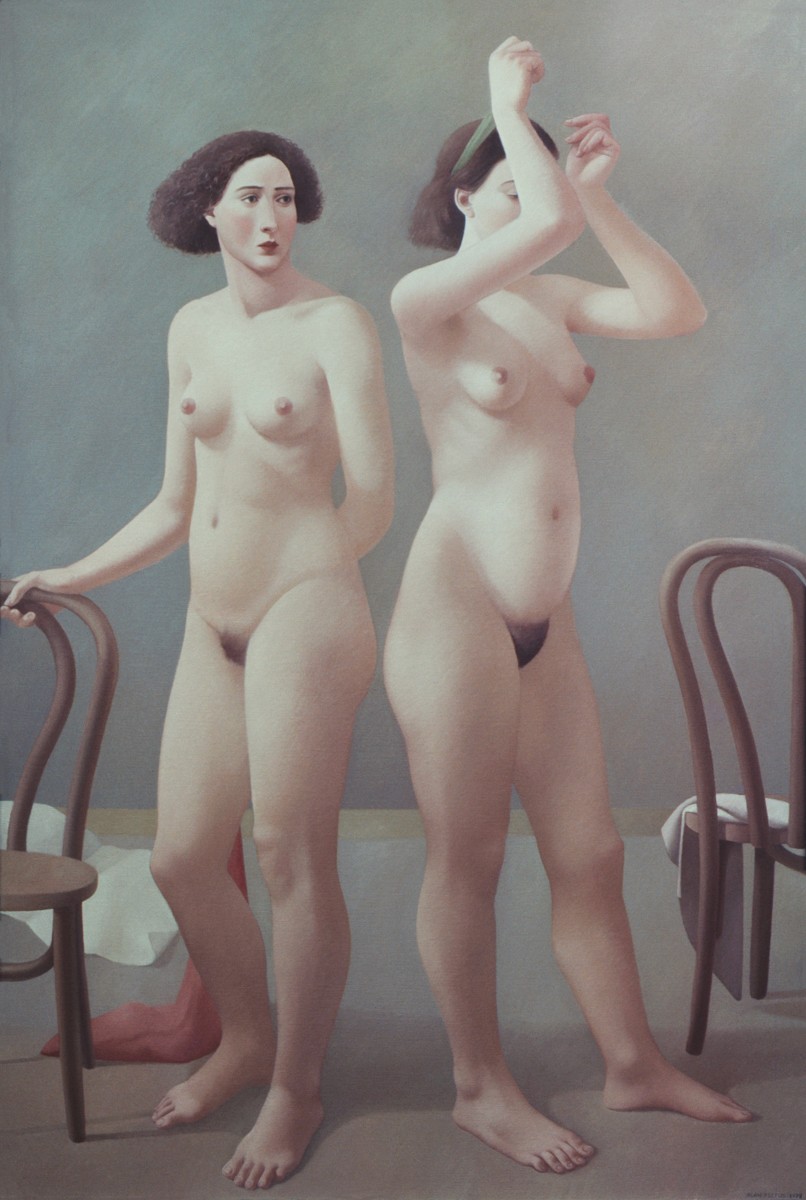

Waiting, 1975-'76, oil on linen, 70 x 56 (178 x 142 cm)

Collection of the Oklahoma City Museum of Art, OK

Two Women, Two Chairs, 1978-'79

oil on linen, 60 ½ x 40 ⅕ inches (154 x 102 cm)

Three Women with Pear, 1981-'82

oil on linen, 70 x 48 inches (178 x 122 cm)

Collection of the Katzen Arts Center, Washington, DC

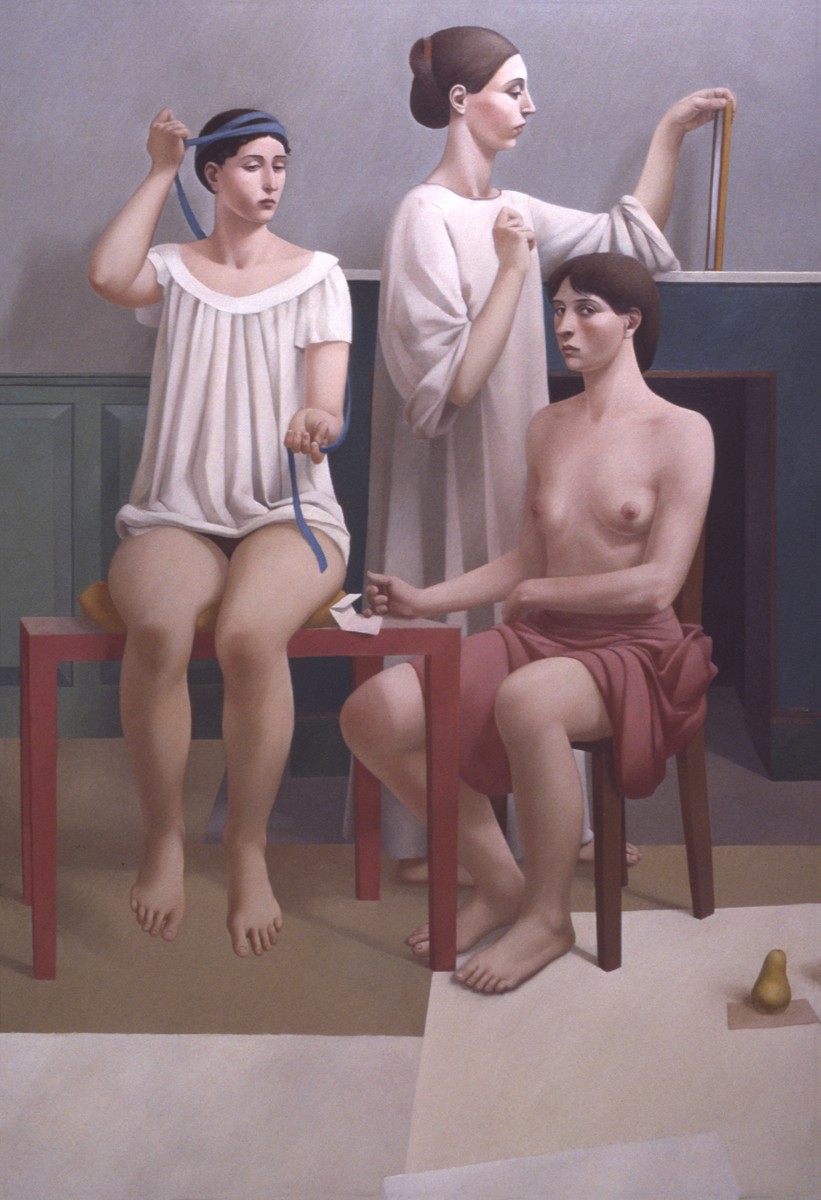

Two Women Standing, Greensleeves, 1982

oil on linen, 60 x 44 inches (152 x 112 cm)

The Announcement, 1983

oil on linen, 36 x 28 inches (91 x 71 cm)

The Landscape Painting, 1986

alkyd and oil on linen, 70 x 48 inches (178 x 122 cm)

One Afternoon in Tuscany, 1986

oil on linen, 70 x 48 inches (178 x 122 cm)

Untitled (Portrait of a Young Woman), 1986–87

oil and alkyd over lithograph on Arches paper

11 ⅛ x 8 ⅝ inches (28 x 22 cm)

Collection of the Wichita Art Museum, KS

The Room With Rose Wallpaper, 1987

oil on linen, 48 x 70 inches (122 x 178 cm)

The Day Lily Room, 1987

alkyd on linen, 48 x 70 inches (122 x 178 cm)

Catalogue Essay for

ALAN FELTUS: RECENT WORKS

Wichita Art Museum, Wichita, Kansas

October 25 — November 29, 1987

by Howard DaLee Spencer

INTRODUCTION

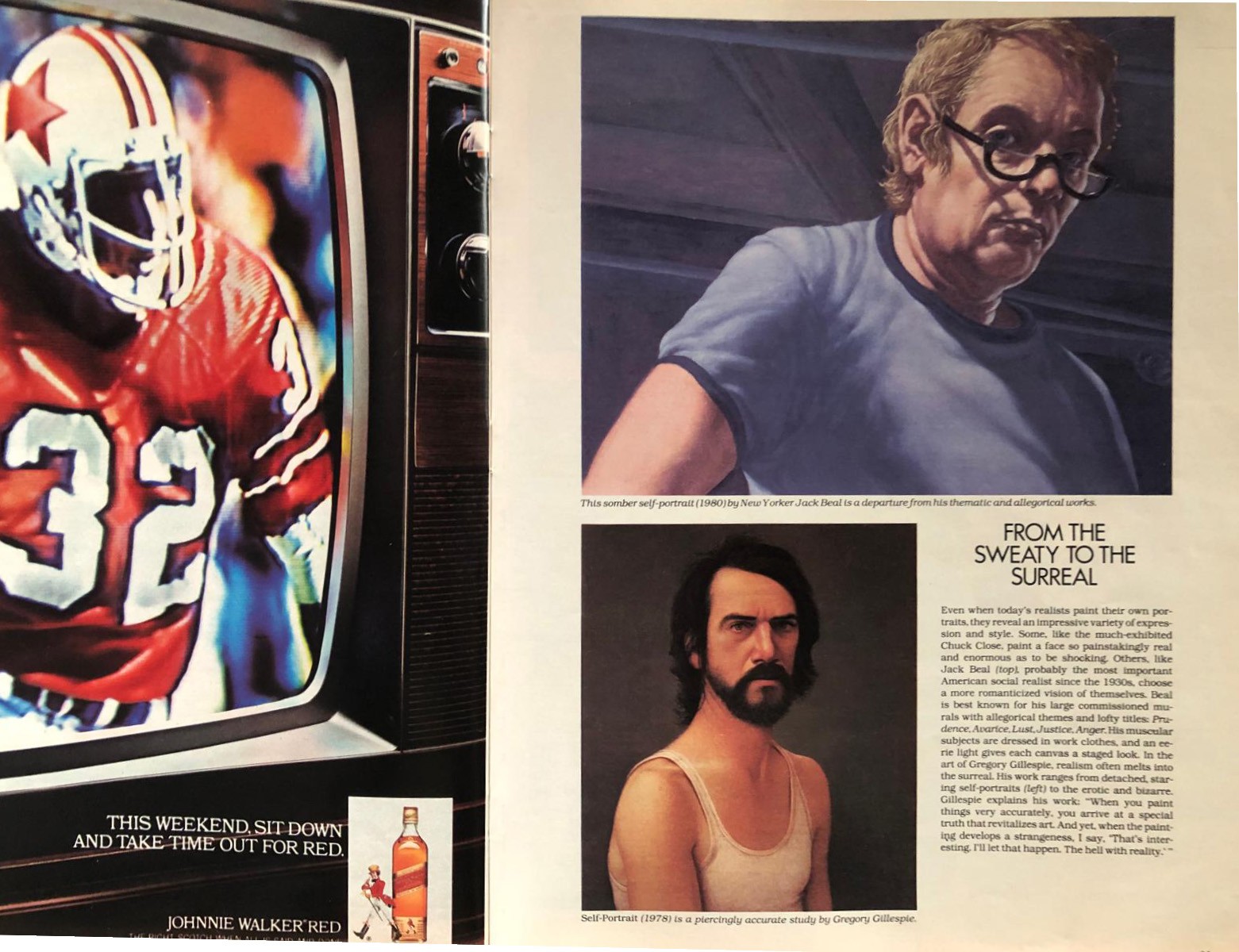

Alan Feltus is among the most distinctive and important figures in contemporary American figure painting.

Over the last two decades his reputation has grown as he has successfully directed his art along a uniquely imaginative path. His paintings can be found in the collections of many major museums and have been shown in nationally significant shows. Two of his works were included in the Wichita Art Museum's exhibition, A Decade of American Realism: 1975-1985, and were among the most popular pieces in the show.

The basic direction of Feltus' art was established by the early 1970s when he began a series of paintings featuring enigmatic figures of women in austere interior settings. Since then his paintings have gone through a period of increasing technical refinement with marked modifications in fundamental imagery. The current exhibition, Alan Feltus: Recent Works concentrates upon the paintings and drawings executed since the early 1980s and at the same time, for the sake of clarity, includes some works dating from earlier stages of his career.

The Wichita Art Museum is indeed privileged to present this exhibition which includes the largest number of Feltus paintings shown to date. The Forum Gallery in New York City has represented Mr. Feltus for quite a number of years and has been of immeasurable help with this exhibition. I wish to express my gratitude to the museums and the many individual collectors who have generously loaned their paintings for this presentation. I particularly wish to thank Alan Feltus and his wife, Lani Irwin, for their hospitality and assistance with the organization of this exhibition.

ALAN FELTUS

The art of Alan Feltus is basically a study in balance.

Feltus is driven as an artist to work and rework each and every detail of a painting until all elements conform to a state of harmony and equilibrium. Even though he sees the creation of art as a classic struggle which can never be simple or easy, Feltus feels a painting fails if that struggle remains evident in the finished work. For him the essential core of the artistic battle and the greatest mystery of art is the balance between the Dionysian and the Apollonian, and that balance is reflected throughout his work.

Perhaps the appreciation for order and balance in his art developed as a result of the absence of these qualities in his childhood and adolescence. He was born in Washington, D.C., in 1943 but moved with his family to New York City soon thereafter. When Alan Feltus was only seven years old, he and his mother were deserted by his father, a public relations man. Feltus' mother also worked in public relations, but met with only erratic business success. She apparently was a woman with upper middle class tastes and social connections, but frequently earned only a poverty level income. Because of their unstable economic condition, Feltus and his mother were often forced to change address and sometimes had to move in with friends. Feltus rarely had the chance to attend the same school for more than a few months and consequently suffered both socially and academically.

He grew into a shy, daydreaming youth who loved art and museums, and whose imagination could find magic on every New York City street corner. Although his mother was not an artist herself, she liked art and knew many artists in Manhattan. Feltus sometimes lived in the same apartment building with artists, and he frequently visited their studios. By the time he had reached his teens, Feltus had become a common figure at gallery and museum openings which he attended with his mother and her artist friends. During his senior year of high school, Feltus and his mother lived in Italy, where he was exposed to many great works of art from the past. He decided to seriously pursue a career as a painter. Feltus obtained a B.F.A. degree from the Cooper Union in 1966 and went on to earn an M.F.A. at Yale in 1968. After teaching two years at the Dayton Art Institute, he returned to Europe to accept a Prix de Rome Fellowship for painting at Rome's American Academy.

Feltus' highly successful career as a painter and teacher began with his return from Rome in 1972. He taught at American University in Washington, D.C., from 1972 until 1984, when he was able to pursue his painting career on a full-time basis. Feltus began his association with the Forum Gallery in 1973, and has been regularly featured in one-man shows at that gallery. Prior to Feltus' studies in Rome, his art was strongly influenced by Surrealist imagery. And even though he painted female figures, he was just as interested in still life compositions and collage. Since his Rome Fellowship, his work has focused exclusively on figure painting and his Surrealist interests have been much less evident.

Feltus' art is somewhat like a Baroque fugue in that it concentrates upon a few fundamental themes which he uses within a set of tightly structured constraints to focus upon subtleties rather than extremes. The basic Feltus painting features one or more women, nude, partially nude or strangely costumed, in a shallow interior setting which displays a small number of personally significant, recurring artifacts. The entire composition is often inspired by masterworks from the Renaissance or classical antiquity, but the end product grows from Feltus' imagination and is neither a copy of another painting nor a representation of actual living people.

Feltus is reluctant to go into detail about his motivations and the reasoning behind his use of a few selected themes to create his art, but he explains his paintings thus:

...I am deliberately avoiding direct reference in the sense of who people are and what they are doing...

I'm not determining what they are doing or why they are there, why they are sharing this space together or doing something. They (the figures) are generally not communicating or touching... they are not specific people or models... the lighting in my paintings is also without reference... it is light for the purpose of defining form, but not light defined in itself by a lamp or a window... There is no story... I guess it's the way I like to experience the world. I like to look at things and I don't need to know too much about those things.... For me it is a real world I am creating... To me they do have an air of mystery about them. The mystery is important to me... (my paintings) all seem to have a sense of stillness or quiet. And, I don't feel I have a need to unravel the mystery... I may be curious, but I am also more able than other people... to watch a movie on television and walk away from it and not know how it ends.... I tend to be able to read a novel half-way and put it aside and not go back to it (1).

In some ways Feltus paintings are almost as great a mystery to him as they are to us. Any interpretation of the paintings is dependent upon the beholder's know-edge and imagination, and Feltus sees this variety of possibilities as one of the most important and satisfying aspects of his work. He is never totally aware of all the possible images his paintings inspire. Feltus' imaginative subconscious wells up images and ideas, but he imposes upon these musings an artistic understanding of order and structure that is uniquely his own.

Although his paintings appear well thought out and tightly planned, each is a metamorphic synthesis resulting from many creative transformations directed toward achieving the balance of a finished work of art. This intuitive approach to painting reflects Feltus' earlier interests in Surrealism since it is not too far removed from the automatic painting favored by some Surrealist artists as a means of exploring their subconscious through their art.

Although Feltus' paintings are the product of his imagination, much of the inspiration for them comes from great works of art from earlier periods. Like most artists he has long maintained an extensive reference file that focuses upon his particular interests. His file contains photos and postcards of Greek and Roman sculpture from classical antiquity to which he refers when creating his paintings. Feltus' admiration for such Renaissance masters as Piero della Francesca, Giotto and Paolo Uccello can be seen in his art. Feltus has noted, "I wish my paintings to have a magic and order like that found in Piero della Francesca's Flagellation... (2) But Feltus does not attempt to paint in the manner of Piero or any other artist. Feltus stresses the importance of the intuitive imagination which he invests in each of his works regardless of their inspirational sources:

My paintings, however, are not constructed according to systems of geometry, as Piero's were, but compose themselves as they evolve from state to state. The changes result from intuition. Intuition is much the same as uncertainty, but one must realize that a painter's whim and anxieties are informed by years of experience not only with the making of paintings but also the study of paintings by masters (3).

The artists whom Feltus most admires are not restricted to classical times or the Renaissance but also include artists who have transcended the limitations of decades and have been consistently good…(4) by remaining individuals and not going along with the crowd. His favorite artists are "deliberate architects of pictorial space…”(5) who "refuse to take reality at face

value.”(6) Feltus especially enjoys Sleeping Gypsy by Henri Rousseau which captures for him a magical reality unbounded by nature's restrictions. In talking about this painting, Feltus notes:

I feel that Rousseau in that painting is not a naive painter... it seems like pure poetry in imagery, so it seems more sophisticated... than the paintings of his contemporaries, the Impressionist painters, and I like a lot of their works... I think good painters have respect for tradition, the history of art….

There are painters in every period that I like and painters that I don't like, and I am fascinated also by the differences within a period.... I don't think it makes any sense to assume that pre-twentieth century art is meaningless to an artist today, because it has to be a part of us.... I think vou have to be a part of your time and take from what interests you in other times.(7)

Even though Alan Feltus does not think that any of his college instructors markedly affected his work, he does sincerely admire the art of contemporary artists whose work he sees as seeking the same ends as his.

Some of these contemporary Realist painters have been inspired by the same classical and Renaissance masters that have influenced Feltus, and have independently arrived at similar imagery or themes. The mysterious figure paintings of the French artist, Balthus, have left their mark upon the work of many contemporary painters, and have indirectly affected Feltus' paintings as well. Balthus influence can also be seen in the work of the contemporary American Realist painter, William Bailey. Feltus sees Bailey as a kindred spirit whose art has in some ways developed on a parallel course with his own. Balthus, Bailey and Feltus all paint mysterious nudes in strange and confining interior settings, but each artist has remained quite individual in his approach to this theme. Balthus' paintings have an undeniable erotic aspect and Bailey's work retains a subdued but strong sensuality. But Feltus goes to extraordinary lengths to remove from his paintings anything overtly sensual or emotional. His unusual sense of detachment sets his work apart from that of other contemporary Realist painters whose work, by comparison, appears extravagantly baroque.

In Two Women, Two Chairs (figure 3) from 1979, Feltus uses the composition of two female nudes and two chairs as he did in Two and a Half. Unlike the earlier painting, however, in Two Women, Two Chairs there is no hidden third figure. In this painting the delineation is more tightly rendered and the brushwork, less painterly. The proportions of the figures are more delicate and their flesh tones, more natural. Even the plain wooden chairs have become more elaborate and demonstrate a growing interest in representing details.

Three Women with Pear (figure 4) dates from 1981-1983 and features the clothed and partially nude figures that are commonly found in Feltus' later works.

The obscure gestures and poses of the figures are now made in association with stage props. One has a piece of paper and another, a ruler-like object. The third wraps her head with a ribbon. The women are now placed in a considerably less sterile environment. This room has a fireplace, a table and chair and wainscoting. The floors define space with squared-off areas, increasing the illusion of depth.

Each figure in Three Women with Pear shares a degree of resemblance that suggests a common ancestor. This family resemblance has been noted in many of Feltus paintings. The features are not close enough, however, to give the impression that the same model is portrayed several times in one painting. Artists sometimes unconsciously create images in their own likenesses even when they are working on another person's portrait.

Jungian psychologists tie this effect to the anima and the animus.(9) The anima represents the feminine side of the male personality and the animus is symbolic of the masculine part of the female personality. These opposite sides of self-identity can often find an outlet for expression in such activities generated in the right side of the brain as painting, music and the arts in general.(10) Since Feltus almost exclusively paints images of imaginary women, the psychological aspect of the anima as the artist's Muse may have some validity when applied to his work. Some people see a resemblance between self-portraits by the artist and the general features of his figures, but a practical explanation may be in part responsible for this visual similarity. Like many other artists, Feltus has found himself to be the least expensive and most readily available model. He keeps a mirror in his studio and uses his reflection to capture nuances of expression and gesture in his paintings. Consequently, all of his paintings are partially self-portraits, and that fact alone would account for his subjects' similar features.

Costumed figures who resemble dancers, actresses or perhaps circus performers are featured in Two Women Standing, Greensleeves (front cover) from 1982. An analogy to dancers is often made when discussing Feltus' figures for they exhibit a feeling of physical self-awareness and confidence. Their gestures and body stances are rationally based upon a solid center of gravity and suggest the studied behavior and conservation of energy learned by professional dancers. Feltus' interiors are designed like many modern stage sets with sparse furnishings and simple backdrops. Some enigma is created by the costumes of the women in his paintings.

The dance, theatre and the circus all have an element of mystery that Feltus seeks to include in his art. Many of the costumes suggest a circus influence which makes them inherently timeless because they are designed to play a role and not to follow fashion. Feltus admires the work of Italian film director, Frederico Fellini, whose Surrealistic movies are often inspired by the circus.(11)

The backdrop in Two Women Standing, Greensleeves is handsomely defined with geometric bands and squares that are much like the designs used in such Roman frescos as the murals in the Villa of Mysteries in Pompeii. These bands act to reinforce the shallowness of the background space and push the figures forward to a point near the picture plane which gives them a more solid look than if they were in front of a deep perspective.

The Villa of Mysteries frescos have a special significance in Feltus' work that goes beyond their inspiration of design elements. The frescos are painted in a style similar to that of Feltus. Both use a comparatively flat and opaque painting technique and both portray their subjects in a limited depth of field. The figures in the frescos also depict nudes and semi-nudes who seem to be acting out mysterious rituals. The symbolism of the murals in the Villa of Mysteries was probably ambiguous even to the initiated. But the murals are usually interpreted as depicting ceremonies from the Eleusinian mysteries held in honor of Demeter, Persephone and Dionysus. The Eleusinian mysteries as personified in Dionysus were the emotional counterpart of the Apollonian rationalism that inspired ancient Greek philosophical thought. These murals, though irrational in their symbolic associations, are stylistically inspired by Apollonian order and classicism. The murals em-bod irrational ideas within a highly rational structure.

This apparent irony offers important insight into the nature of Alan Feltus' art.

The Announcement (figure 5) from 1983 depicts a much more complex set of relationships than earlier works like Two Women, Two Chairs. Feltus uses folds and creases in fabrics to define form, but shows little interest in the tactile qualities of the materials. Since the early 1970s he has used curtains and draped fabrics to create organic compositional forms, but in the 1980s he increasingly used clothing as a means of revealing the human forms that are beneath the fabrics. Tromp l'oeil effects through the use of postcards on the back wall stress the very shallow depth of field. The tacked-up image on the left is a photo of a painting by Alan Feltus wife, Lani Irwin. Feltus paints photos and postcard images of works by other artists he admires and enjoys this excuse to "copy? other artists' paintings. Feltus also uses tromp l'oeil elements in a Surrealist-inspired manner by including in his paintings strange objects that hold unexplained personal meanings.

The photo on the right side of The Announcement represents the airplane used by Kansas aviatrix, Amelia Earhart, for her doomed attempt to circumnavigate the globe. The mystery of her flight has taken on the aura of a Greek tragedy. Like a modern-day Icarus, Earhart seems to symbolize the brightest light of mankind's rational and technical achievements; but, even so, she vanished in the hour of her triumph in a manner that remains mysterious and incomprehensible. Her epic story shatters our golden illusions of mankind's god-like omnipotence, and we experience a sense of primal loss that heightens our own awareness of universal human frailty.

Profound grief may in part be at the bottom of the atmospheric stillness that permeates Feltus' paintings.

Feltus' series of small portraits (figure 6) are directly connected to Coptic funerary portraits from the later years of the Roman Empire.(12) These ancient encaustic paintings exude an atmosphere rich in mystery and stillness that Feltus finds appealing. Inspired by these paintings, he created a handful of lithographs which he has over-painted to produce dozens of individualized and iconically powerful portraits. His paintings seem to capture the same timeless sense of elemental loss and stoic simplicity found in the Coptic images.

The Landscape Painting (figure 7) and One Afternoon in Tuscany (figure 8), both from 1986, show many of the elements which have been the focus of his recent work. His paintings have become brighter, more colorful and much more detailed. Figures of women are increasingly elongated and now seem closer to Mannerist or Gothic proportions. Feltus has lessened the contrast between highlights and shadows in his figures and has given their flesh tones a more natural color. His con-trolled, visible brushwork has now been minimized in favor of a more solid sense of form. Pieces of paper, photos, or squares of carpet remain in his paintings to emphasize the dimensional floor space, and furniture still is used to help define the room's perspective. In contrast to his earlier works, however, the rooms seem packed with detailed still life setups and tromp l'oeil studies. Even though more objects are present, the space feels less constricted due to the greater depth of field in the rooms and the introduction of windows that make the interior spaces appear less cloistered. The windows also relate to a long tradition of portraiture where the subject stands before a window magically opening upon a landscape in deep perspective. In the early Renaissance such landscapes often included distant views of buildings or villages that looked more like a model train set than like real houses or communities.

The views out the windows of Feltus' rooms also appear as an artificial world. This effect is partly due to his emphasis upon form over textural differentiation, but there are philosophical implications which might also be taken into account.

Feltus' paintings create a world that lives by its own definitions and is different from the reality of his tromp l'oeil images or the world in which we function. The subjects of the tromp l'oeil often more correctly approximate textural reality than the other parts of Feltus' painting. This classical formality reflects a level of reality that is too unblemished and perfectly formed to be subject to our normal world's laws, and stresses the unreal atmosphere of these Realist paintings.

A new direction in Feltus painting is suggested in The Room with Rose Wallpaper (figure 9) and The Day Lily Room (back cover), which both date from 1987. The women in his paintings have been monumental in their proportions, stance and demeanor, adding to their remoteness. These most recent figures do not have this larger-than-life presence but have attained a more human appearance. Feltus' palette is becoming warmer and tends to humanize the figures. These changes add a sensuality to the Feltus paintings that has been missing in earlier works and imply an important shift in attitude. Feltus' compositional space now seems less classical structured and more organically fluid with its forms. He introduces new elements in his painting such as the wallpaper patterns which appear in these two paintings for the first time in his work. The perspective of the bed in The Day Lily Room breaks through the surface plane with a dramatic overhead point of view that brings the viewer into the compositional space.

These paintings suggest that Feltus may be gradually moving away from some of the tightest constraints of his personal classicism and is exploring a more naturalistic style of Realism.

Throughout his career, Alan Feltus' paintings have reflected his continuing desire to achieve a sense of order balanced with an underlying feeling of mystery.

This combination gives his works something more meaningful than the mere appearance of classical style or elegance. By removing as much as possible the sensuality associated with the nude, Feltus allows his figures to more closely approximate the art of classical antiquity whose goal was to bring the human form to a level of divine perfection unbounded by the limitations of mundane reality.

Feltus' women seem to live in a world apart, separated from reality by their unexplained, mysterious gestures. Our world of human affairs appears insignificantly trivial or perhaps simply boring to these mysterious females. They abide by their own set of rules in their own dimension of reality. The mystery of these goddesses lies in their aloofness and inaccessibility.

Like the Sphinx of mythology, Feltus' figures hold many secrets into which both the viewer and the artist inquire at their own peril. Yet, this inquiry is a significant part of the artistic experience, and for all that can be learned the artist knows there is always more that can never fully be comprehended.

As the ancient thinkers well understood, beneath the classical order of harmony and form always lies the madness of chaos and irrationality. Feltus' paintings aptly demonstrate his profound awareness of the subtleties of this seemingly eternal balance between the Dionysian and the Apollonian aspects of human nature.

The attempt to understand this dichotomy may strike closely at the heart of mankind's essential nature as expressed through his art. The ancient Greeks envisioned mankind as inherently composed of a light and a dark aspect, both of which must inevitably manifest themselves in all forms of human expression. The Muses of mythology, like Feltus' women, symbolized this universal truth for they brought harmony and order as well as divine madness as their gift to the artist. The Greeks invented the theatre as a means of celebrating the Dionysaic festival, and the stage set appearance of most Feltus paintings offers an obvious correlation, especially when combined with imagery from the Villa of Mysteries.

Universal truths function on a different level of reality than we normally experience, and the artist uses symbolic imagery and his creative imagination to bring these concepts to our level of understanding. Feltus' art balances the irrational with the rational, the mysterious with the comprehendible and the chaotic with the con-trolled. His work holds up a mirror to our own secret selves and allows us to better understand the nature of art and perhaps the very essence of the human spirit.

—Howard DaLee Spencer

REFERENCE NOTES

Alan Feltus, interview at artist's studio in Hughesville, Maryland, March 18, 1987. Wichita Art Museum Files.

Jill Wechsler, "Alan Feltus: The Mystery in Paint-ing," American Artist 44 (April 1980): 62.

Ibid.

Alan Feltus, interview.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

M.-L. von Franz, "The Process of Individuation," in Carl Jung (Ed.), Man and His Symbols, (New York: Dell Publishing Co., 1979), pp. 186-207.

Julian Jaynes, The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, (Boston:

Houghton Mifflin Company, 1976), pp. 100-125.

Alan Feltus, interview.

Ibid.

Published by the Wichita Art Museum

Printed by the Rand Publishing Company, Wichita, Kansas

Copyrighrt © 1987 by Wichita Art Museum

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number: 87-51360

ISBN: 0-909324-32-6

ALAN FELTUS, NEW PAINTINGS

by Edward Lucie-Smith

Perhaps because figurative art is out of favor with many of the aesthetic theoreticians of our own day, people have begun to forget that the figurative in painting, besides being a reflection of what we perceive in the world that surrounds us, is also a way of ordering our mechanisms of perception. Certain exceptions are of course made, in the very midst of this neglect. One is the work of the great 17th century Frenchman, Nicholas Poussin. The response to the great Poussin retrospective, seen in Paris and London during 1994-1995, showed how keen an appetite there is now for art of this type.

Though Alan Feltus draws some of his titles from classical mythology, his work, in contrast to Poussin's, is essentially domestic in theme. His characteristic subject matter is not the gods of the Greek and Roman pantheon, but figures, almost inevitably female, in the studio, or in quasi-domestic settings. Like the personages in Poussin's work, however, these figures serve as a vehicle for what would now be dubbed "abstract" concerns -- a play of spatial relationships, a subtle balancing and rhyming of forms. To such concerns, however, are added others. These additions are what the choice of the figurative mode allows. Feltus's work often—indeed invariably when two or more figures are involved—has an implied narrative, which is more engaging because its terms are ambiguous. One painting in the present exhibition is called Moment Between, which calls our attention to something that would in any case be obvious: the two women shown are caught in a transitional phase, perhaps connected with the letters and papers scattered on the floor. Some action has just been completed, most probably by the odalisque-like figure to the left. Another activity is about to be initiated by her companion on the right, shown in a pose that indicates that she is about to rise to her feet.

The literal-minded spectator may perhaps be disconcerted by the fact that the figures, despite their role as actors in a narrative, are also somehow impersonal. The women always conform to the same physical type, possess the same calm Italian beauty of feature, and, especially when nude or nearly so, offer an idealized version of the human body. The fact is, nevertheless, that Feltus's paintings belong to a very well established tradition, not only in the history of European art (as my comparison to Poussin suggests) but in the history of modernism.

The comparison most often suggested, when Feltus's work is discussed by critics, is one with Balthus. A general resemblance to Balthus's paintings, especially the earlier ones, certainly exists, and one knows that this is an artist whom Feltus studies and admires. Yet there are also very obvious points of difference. Feltus does not share Balthus's perversity; his eroticism is of a different and less obsessive kind, his relationship with the classical tradition much more straightforward. In trying to find an exact stylistic location for Feltus's paintings I would point first to an artist who lies just outside the boundaries of Modernism—to the figurative work (as opposed to the landscapes) of Camille Corot. It is significant that this aspect of Corot's work attracted little attention until the rise of the Modern Movement. It was Corot (almost as much as Ingres) who provided the inspiration for Picasso's brief but dazzling Neo-classical phase of the early 1920s. He was also important to the post Fauve Derain; that is, to the aspect of Derain's work so much appreciated in the 1920s and 1930s which is now, though only slowly, being rediscovered.

If Corot, Derain, and Picasso seem to be exemplars, so too do some of the Italian painters who flourished during the first half of the present century. Two who come to mind are Felice Casorati and Mario Sironi. These in turn refer Feltus back to the great artists of the Renaissance: Giotto, Piero della Francesca and Uccello, and back beyond them, yet again, to Greek and Roman sculpture. It comes as no surprise to learn that Feltus's own paintings are essentially constructs, dependent not on the presence of actual models in the studio, but on the artist's familiarity with the whole tradition of Western art. Poussin, essentially, worked in the same way. We know of no studies from life by him, but of many compositional studies, some clearly based on the engravings of earlier masters.

Looking at Feltus's work we enter into a dialogue both with "classical" aspects of Modernism and with the whole history of Western art. What he does is not only beautiful in itself, but serves as a reminder, more necessary now than at any previous moment, of the essential underlying continuity between 20th century art, however radical this may strive to be, and what artists did before the notion of an avant-garde was formulated.

—Edward Lucie-Smith

Edward Lucie-Smith is one of the best known writers today on international contemporary art. Among his more than sixty art books are the following: Movements in Modern Art Since 1945, Eroticism in Western Art, 20th Century Latin American Arts, Race, Sex, and Gender in Contemporary Art, ArToday, and Art Tomorrow. He is also an internationally recognized photographer, poet, lecturer, curator, and art critic.

Moment Between, 1994, 39 ¼ x 55 inches (100 x 140 cm)

AMERICAN ARTS QUARTERLY, SUMMER 2002

Alan Feltus's figures seem both reticent and freighted with psychological meaning. His characters are dark-haired and wary-eyed, and both sexes bear a family resemblance to the artist as depicted in his self-portraits. The figures are deployed, singly or in couples, in simplified settings. In Me and Mrs. Jones (2001) a man and a woman stand close together yet distinctly apart; their bodies turn toward each other, but they stare out at us. Their body language simultaneously suggests intimacy and estrangement. There is more fresh air in Two Trees, Two Chairs, Two Arms (2002), in which a solitary, contemplative young woman sits in front of a landscape.The geometric forms of the title provide a kind of scaffolding through which we view the soft forms of earth and sky. We seem to have entered a world familiar yet slightly uncanny, idealized yet pervious to the uncertainties of human relationships. While there is little in these images of historicist pastiche, Feltus's characters have a courtliness that suggests the early Renaissance, an era that is part of the air the artist breathes. Feltus, who was born in Washington, D.C., in 1943, has lived in Italy since 1987. His adopted home, Assisi, offers a constant source of inspiration — the Basilica of San Francesco, with its frescoes by Cimabue, Giotto, Pietro Lorenzetti and Simone Martini. In an unusually straightforward painting, Autumn Sel-Portrait, Assisi Earthquake (1997), he depicts himself with the rescue pass he wore as a volunteer in the aftermath of the natural disaster that devastated this beloved town. In another image from that period, Giotto Earthquake Portrait (1998), the grave young woman in a russet smock and turbaned scarf stands in front of a simulacrum of a Giotto fresco featuring a half-collapsed church and a group of mourners. Her long fingers reach out of frame, and she has the gravitas of the women at Christ's tomb.

The spirit of the early Renaissance permeates Feltus's work well beyond the occasional image-within-an-image quotation. Although his figures wear contemporary clothes and project modern anxieties, their emphatic, enigmatic gestures recall the stylized body language of earlier art. Mural painters had to convey meaning and emotion clearly to an audience at a distance. The conventions of physical rhetoric—codified in the ritual movements of the Christian liturgy and the madra of classical India—provided a base language. But artists also used the spontaneous human gesture, the involuntary spasms that grip us when we are subjected to strong emotion. Giotto effectively combined the two modes, as Moshe Barash has documented, infusing "gestures that appear to be 'conventional' with the spirit of life, of an immediate, almost urgent, psychological reality," while maintaining, at the same time, a "quality of emotional restraint" that carries the solemnity of ritual (1). Feltus's choreographed gestures have some of this quality. The elaborate positioning of his figures' legs, arms and hands hints at a rich psychological subtext just out of our—and perhaps their—reach. His movement vocabulary functions in a private, secular milieu.

In a recent e-mail Feltus offered a few clues. In some images, he suggests, the represented couple could be seen as the artist as an adolescent and his mother, "private material I was interested in dealing with through the meditative process of painting," or the artist with "an imaginary lover, like Gorky's Self with Imaginary Wife." (2). (The Gorky painting, c. 1929, is in the collection of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.) Arshile Gorky's (1905-48) use of the word imaginary suggests the woman may be a manifestation of the anima, an ideal soul-mate, an avatar of the muse. Another Gorky painting, The Artist and His Mother (1926-29, Whitney Museum of American Art), indicates how artists transform the raw material, not just of an actual face and body, but of a pre-existing image into the components of a painting. The Artist and His Mother is based on a photograph taken in Armenia in 1912 showing the boy Gorky standing next to his seated mother in a photographer's studio. Through a decade of drawings and oil sketches, Gorky subtly manipulated shapes "dissected from the photograph" (3) to create a poignant memory picture. Feltus, who never paints directly from models, similarly distances himself. The only exception to the model prohibition is when he looks at himself in the mirror. Otherwise, his references are to photographs of other artists' work, especially from the early Renaissance.

The situations Feltus depicts include private encounters with the muse, an externalization of the feminine that comes, he remarks, "from the inside." But the woman he depicts also has a number of art historical antecedents. Wendy (1999) replicates the tilt of the head and hand gesture from Botticelli's Birth of Venus; her rapt, slightly unfocused gaze has an intensity reminiscent of the twentieth-century eccentric figurative painter John Graham. In The Painter and His Muse (2000) the leggy woman in a short shift has the grace of a modern dancer, but her delicate hands and etched profile suggest the Italian Renaissance. In an epilogue to a recent book on Piero della Francesca, Feltus's painting is reproduced to illustrate the long afterlife of the Renaissance master's influence. Inspired by Piero's ability "to use the crystalline world of mathematical purity to describe the numinous quality in human life," modern painters as diverse as Seurat and Balthus have explored the mysterous relationships of figures in space (4).

In Feltus's Time Together (2001), the almost naked muse sits on a simple chair. Her arms are raised as if to arrange her hair. Her legs are crossed; her feet do not touch the ground but hover, somewhat mysteriously, casting a shadow on the rumpled white material below them. She gazes out of frame, acknowledging neither the viewer nor her companion. Her profile has a classical simplicity, as if she were a maiden escaped from a Grecian urn or a Renaissance marriage portrait. The young man who sits behind her on a low bed has one leg drawn up; he holds a letter, blank side out, to his chest. The blank letter, a recurring motif, is an economical way of alluding to a breakdown in communications, or perhaps the inaccessibility of personality in even the most intimate relationships. What the relationship is between these people and what the emotional temperature in the room at this particular moment maybe remain tantalizingly vague. Yet the play of shapes has its own logic. The room seems so shallow that the man and woman might be figures in a frieze. Her bent elbow overlaps his bent knee. His hand echoes the shape of his bare foot, which visually impinges on her thigh. The compositional compacting of body parts communicates intimacy, yet there is palpable emotional distance between these characters.

Feltus's figures may emerge from his own psyche, but they become known only through the process of painting. The content of these scenes is co-existent with and developed through the act of composition. The artist explains, "I search for form and balance elements within a space that has always to relate to the edges of the canvas. What narrative there is unfolds simultaneously within this struggle to find visual meaning." The shape of an arm may communicate estrangement or longing, but that movement is also, even primarily dictated by a visual imperative. The past is alive in these paintings, visible in the skill of the artist and in his subtle allusions to older artists. Yet Feltus's tableau are unique. His women and men have escaped the constraints of time to inhabit a world of formal purity and becalmed emotion. "Alan Feltus: New Paintings" can be seen at the Forum Gallery, 8069 Beverly Boulevard, Los Angeles (September 6-October 12, 2002), and at the Forum Gallery, 745 Fifth Avenue, New York City (December 12, 2002 - January 18, 2003). www.forumgallery.com

Notes

1. Moshe Barash, Giotto and the Language of Gesture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), p. 13.

2. E-Mail correspondence, April 2002.

3. Harry Rand, Arshile Gorky: The implications of Symbols (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991) p. 29.

4. Marilyn Aronberg Lavin, Piero della Francesca (New York: Phaidon, 2002) p. 336.

Gail Leggio is Associate Editor for American Arts Quarterly, published by the Newington-Cropsey Cultural Studies Center.

THE MIRROR AS MUSE

Alan Feltus composes classically serene pictures that describe the silences between characters—and the artist’s own meditative engagement with the art historical past.

By Maureen Bloomfield, Editor of The Artist's Magazine

Alan Feltus’s pictures are serenely modulated pas de deux, with figures who are mirrors of each other engaging in an arrested dance. The figures are less particular people than archetypes (one thinks, for instance, of the myths of twins and of animus and anima, the male and female aspects of the soul). So precisely calibrated are their spatial relationships that the figures could be attached with invisible wires; if one were to move, so would the other. When Feltus presents a single figure, she is often portrayed as an artist consider- ing a self-portrait. The artist gazes outward, and the viewer takes the place of a mirror.

The setting for these tableaux is usually a golden interior where pictures on the wall function as windows to an actual Italian landscape or to the art historical past. Feltus quotes the American art critic Hilton Kramer, who maintains that in art “there are no virgin births.” Indeed, Feltus’s own influences are diverse: from Cycladic sculpture to Giotto; from Titian to Giorgio de Chirico; from Arshile Gorky to Balthus and Lucian Freud. Feltus puts it succinctly, “I have always understood that art comes out of art.”

As a young man, Feltus spent his last year of upper school at the American Overseas School of Rome, and two years at the American Academy on a Rome Prize fellowship. Since 1987 Feltus has lived in Assisi with his wife, the artist Lani Irwin. Thus it’s no surprise that his pictures radiate the distinctively Italian palette of the Tuscan, Umbrian and Perugian countrysides, and the beautiful, faded ochre of early Renaissance frescoes. During his initial visits to Italy, Feltus was also impressed by the works of modern Italian masters, less known to Americans, such as Felice Casorati, Giorgio Morandi, Antonio Donghi and Fausto Pirandello.

Once you’ve looked at several of Feltus’s pictures, you will recognize his characters as you would recognize Giotto’s, Fra Angelico’s or Perugino’s. While those Renaissance masters painted episodes in the often turbulent lives of saints, not much happens in terms of action in a Feltus painting—certainly nothing as violent as the tortures of martyrdom. The moment portrayed is suspended—before or after. The mood is contemplative; the setting, calm. In Feltus’s pictures, a relationship or a state of mind is adumbrated, not revealed. Often a character holds a pen or a brush, a letter or a book. Thus, the pictures self-consciously reflect on the crafts of writing and art. Just as a letter contains a message inchoate until it is read, Feltus’s pictures examine the artist’s isolation; they reflect on the solitary deliberation that precedes, accompanies and follows the making of a work of art.

It’s a truism oft repeated that all art reflects its maker, but in Feltus’s case it’s literally true. Instead of employing models, Feltus consults a mirror. His paintings then are, in a way, self-portraits. Another factor is his love of solitude, a habit of mind that would be compromised by interacting with a model. Looking in mirrors is thus a practical alternative. “I need to see something to understand what I’m painting,” he explains, “to understand, for instance, the anatomical structure of the arms and hands, or the face as well. Even female figures have more of me in them than they have of any other references. I do look at photographs I’ve taken in museums of sculptures in many views, and I look through books of art reproductions, but those things never really match the figures I have in the paintings, so I rely more on mirrors.”

While his compositions are classically balanced, with nary a haphazard or wayward element, he uses neither a preliminary drawing nor a grid. “I start a painting without any idea of exactly what sort of figure or figures I will be painting,” he says. “I try to find the figure or figures within the rectangle of the canvas. Once a line breaks the blankness of the new canvas and there’s something to then relate the next line to, I can keep working. (See the step-by-step progression here) A figure is positioned, although tentatively—then maybe a second figure. And line becomes more than line almost immediately. I loosely put in color as the forms are starting to emerge in light and dark, and there begins an endless series of changes and adjustments.” While his works emit a serene finitude, they don’t necessarily proceed toward a straightforward or predictable end. “At a certain point, what looked good in the initial stages now looks rather bad,” Feltus says. “It’s part of the development of every painting that it moves into chaos before emerging again into some- thing acceptable. A metamorphosis has to take place.”

Pre-primed Belgian linen that he and Lani Irwin carried over to Italy is his favorite surface— “good Belgian linen (primed in Belgium by Claessens for Utrecht) sent to New York City, only so we could bring it back to Europe!” When he needs smaller panels, he coats them with rabbit-skin glue and lead-white primer. Color is consistent and distinctive in a Feltus painting, yet he says, “The colors I use are not extraordinary.” The oil paints are from several manufacturers, because a color like yellow ochre can differ from maker to maker, but he uses predominately Old Holland paints. The white he prefers is lead white (often called Cremnitz or fake white). “I start a painting with a limited palette, using lead white, ultramarine blue, Venetian red and yellow ochre. I stay with those three primaries plus white for several layers, during many changes in the painting. When things are more or less in their places, I expand the range of colors a little, but I don’t use a large number of colors.” The medium he uses is a mixture of Liquin, cold-pressed linseed oil and turpentine.

Subdued color, subtle effects, translucent light— Feltus strives for a contemplative mood rather than a dramatic one. He tones down color instead of punch- ing it up. “Most of all I’m after a kind of light in a painting. This light is the result of getting the right balance of colors, as well as adjusting the relationship between what’s in light and what’s in shadow. It’s not a real light any more than

the fgures and the space are real, but there is a quality that’s made through color and light. And I want color to have air in it, so to speak. One feels that the light has air in it.”

Feltus builds up these lucent colors in oil by painting in many thin layers, a process that allows

him to make what he calls “continual adjustments.” He explains: “With oil paints, because they’re slightly translucent, the surface color is made more rich and luminous from the layer or layers of color beneath. That’s easily seen when one compares a finished painting of many layers with an alla prima painting made all in one layer. That isn’t to say alla prima paintings aren’t beautiful. Any kind of technique can be beautiful.”

Design—the proportional arrangement of form and its absence, the ratio between the figures and the ground—is of fundamental importance. In a Feltus painting, the spaces between the figures are as eloquent as points of contact would be in other painters’ works. The artist comments: “My figures fnd their pre- cise spatial relationship to one another largely by virtue of my wanting every form in the painting—be it figure or drapery or shapes between things or whatever—to be ‘right’ in my terms. What that means isn’t so easy to define. I love those paintings in which structure seems more present than the narrative content (the story being told through imagery). In the High Renaissance— for example, the works of Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael, etc.—the structure is less easily seen because the figures and the landscape behind them are so much more lifelike. The awkwardness that seems controlled by the composition in the earlier Renaissance paintings—for example, those of Giotto, Simone Martini or Piero della Francesca–is gone. I like that awkwardness.”

Feltus’s intent is not to convey a naturalistic illusion, but to fabricate a work of art that partakes of artifce and posits its own rules. He describes his way of dealing with composition as “intuitive, rather than using any systems or geometry or grids.” He elaborates: “I’m like an abstract painter as far as composition goes. The forms want to find the most perfect position and relationships possible. That arrangement is com- plicated by the logic of shadows on the floor, the spaces between figures, and the figures’ anatomical structures. But then again, paintings aren’t real and don’t have to fall into correctness the way real things do. A painting can be better when it doesn’t depart too much from the fatness of the picture plane. Contradictions are interesting. Anatomy might be unreal as well. Think of Ingres’s distortions. And certainly there are millions of examples in the history of art where there is less of a desire for things to read as real.”

While Feltus’s pictures may be read as a formal sequence of shapes and intervals between shapes, they partake of the “real” to the extent that they imply a narrative. A clothed man and a naked woman face one another but look away. A drawing board is blank. A letter is held, not read. The message that is missed or waylaid is a recurrent theme. Feltus’s characters speak to the quandary of relationships—between the artist and the muse, the body and the soul, the feminine and the masculine, the lover and the beloved and, perhaps most poignantly, between the painter and the past.

“When I make a painting, I find myself in dialogue with other masters from other places and other periods,” says Feltus. “My influences go back to the very earliest known paintings and to those of our time. The wax encaustic Fayum portraits, painted in Egypt from around 100 to 300 A.D., are as beautiful and as fresh and seemingly contemporary as any painted heads I know. There is no more sophisticated drawing of an animal than the best of those prehistoric cave paintings from Lascaux, and Brancusi is not really better at abstracting from nature than a good Cycladic sculpture. The making of art today is not about the making of something that hasn’t been done before. Even performance and installation art have been around since ancient times. In art as in human nature, there is no progress.”

www.artistsmagazine.com October 2008

INTERVIEW WITH THE PAINTER ALAN FELTUS

***

The Montréal Review, February, 2011

***

Alan Feltus was born in Washington, D.C., in 1943. He studied at the Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia and later earned a bachelor’s degree in fine art from Cooper Union in New York City and a master’s degree in fine art from Yale University. Since 1987 he has lived in Assisi, Italy, with his wife, the artist Lani Irwin. Feltus has had one-person gallery exhibitions in New York City, Los Angeles, Atlanta, Boca Raton, Wichita, and Washington, D.C., as well as in Chicago, San Francisco, New Orleans and Rome. In 2007 the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art staged retrospective shows of Feltus’s and Irwin’s work. Forum Gallery in New York City (www.forumgallery.com) represents him. To see more of his work, visit www.alanfeltus.com.

***

TMR: Mr. Feltus, your paintings remind me of the saying: "The silences speak loudest". How do you achieve this effect in your works?

Alan Feltus: When I was an art student, I became aware of the tendency I had to make very quiet paintings. It was more clear when I was in graduate school because that was when I began painting mostly from within my self rather than painting from observation. In undergraduate school, we all worked from the model or still life. When painting what I observed, my work was in direct response to what I was looking at. On my own, I instinctively painted quiet paintings. I saw there was a clear difference between the earlier paintings made from observation and the new ones. I realized also that I was most interested in quiet paintings by other artists, throughout the history of art. I have to paint quiet paintings. It is who I am. My paintings go through many changes before they are finished. They start quietly and they become more quiet as I find relationships that are right for me and as I refine things toward the last stages of any painting. The quality that I require of my work is largely about this silence.

TMR: What makes an artwork a masterpiece? What is hidden, technically and spiritually, behind the magic of true art?

A.F. We all have differing ideas about what great paintings are. For me there are many things that are important in painting. Composition is very important to me. There are many kinds of composition. If I don't see an order that exists apart from the narrative or subject matter in a painting the painting is not a good painting. In other words, there is an abstract structure underlying any good painting, as I see it. What interests me is often more an intuitive composing, as my own composition is, rather than a geometric framework that holds the painting together. Color and light have to be beautiful for me to love a painting. Magic is more difficult to come to grips with. What makes one painting extraordinary above others can be one of many things. Often I don't really know what that quality is. It might be a kind of rendering that is far more perfect in every way than what I am capable of doing. Or it might be a kind of poetry that I see in a painting that eludes any clear explanation.

TMR: Before you start a work, do you see the image and the message, or it appears later?

A.F. I usually begin a painting without any idea what the painting will be about or what it will look like. However, after many years of painting some things are going to be present in any painting I start. That has to be. So I might begin with some tentative marks with a pale color directly on the white ground of a canvas. I often start with two figures. A few lines set something in motion and I take it from there. It is about how two figures fit within the edges of the canvas. How they relate to one another and the space of the canvas. Everything moves in the first hours or days of a new painting. Actually, things continue to move throughout the painting of any painting. But those first marks set up what continues to be a play with directions and intervals and spaces. Shapes of two bodies and shapes between them and between their contours and any other line in the painting. I might put in a horizontal line that divides wall from floor, and maybe a vertical that is a wall edge. A chair might come in. Those are enough to stay with for weeks. They shift and change and very often are painted out and something else brought in. Most changes are small but they can be as large as taking out a figure or moving a figure to a new place in a painting. One such change triggers many others.

TMR: In an interview you said, "In art as in human nature, there is no progress." What do you mean?

A.F. Great art has been made in all periods, in all cultures. There are cave paintings from Lascaux that depict a cow or a horse that are as sophisticated as a cow or a horse by Picasso or anyone else working in our period. A Cycladic sculpture of a head or a figure is as beautifully abstracted as a Brancusi sculpture. The best of the encaustic Fayum portraits dating back to about 160 AD Egypt are as fresh and beautiful and painterly as any portrait painted in any century. A Roman marble portrait can be as fine a realist portrait as any that followed. A Pompeiian fresco might be as wonderful as a Renaissance fresco. And few frescoes made in our times are anywhere near as beautiful. Ife sculptures from what is now Nigeria were seemingly way ahead of European sculpture from the same century, and are as fine as anything done today. I can't see that art has improved in quality from prehistoric and ancient times to our time.

What does change in art might be the use of new materials, or different ideas, but the quality of art doesn't improve with the passing of centuries. That is very clear to me. Human nature has made no real progress from ancient times to today, it seems to me. War shows that to be so. Our film and TV entertainment is not very different from the entertainment of the gladiators in the colosseum. We are basically the same as ever before. Progress can be seen in technology. Airplanes fly, telephones and computers enter the scene. Illnesses can be cured. Armies have bigger bombs.

TMR: The objects must be illuminated (by light) in order to be seen, René Descartes says in his "Optics." As an artist, how do you understand this idea?

A.F. Light is one of the most important elements in paintings. Nothing can be seen without light. Some art is heard and some is understood through touch but in painting nothing is seen without light. Light in the room allows us to see a painting. Light within the painting, as painted by the artist, allows the viewer to understand form. In paintings light can be the primary subject or a very central part of one's work or it can be one of many elements a painting is made from. Light and color are interdependent. Light has a color that influences all the colors, all the parts of a painting. Light can carry a mood as well.

TMR: Are your works autobiographical?

A.F. A painter's works should be autobiographical. We make what we have to make. Each of us makes art that is different from that by anyone else. I think we can't help it. And the art that is made from deep within the artist can't be other than about what that artist is about. Of course, self portraits are more directly autobiographical by definition than other paintings, yet we are identified as people also by what we paint and how we paint what we paint. There will be some artists whose works are more personal and more about their own thoughts or experiences than others. So someone like Frida Kahlo painted more biographically than Mondrian, however, we can say that Mondrian was very much like what he painted. Only in a different sense.

Because I paint using mirrors, observing parts of myself rather than models, I might say that all my paintings are to some degree self portraits.

TMR: What is the place of the solitude in the life of the artist?

A.F. Not all artists work alone, of course. I value my solitude. In my studio I am surrounded by things that feed me. Books and reproductions, objects. I need to have my own space and a kind of quiet. I might listen to radio while I paint but I am not in conversation with anyone other than myself. It minimizes distractions. I view the solitude of the artist's studio as a luxury. We are fortunate who can choose our work in all respects and create in the privacy of our own work space.

TMR: The works of which writer or poet correspond best to the style of your paintings and who are the influences in your art?

A.F. Ah, I can't answer that question. I don't know that writers influence my paintings. I can tell you that Cormac McCarthy has for years been the writer I like best and that is because I love the richness of his language. He describes a place more beautifully than other writers I have read. His writing reads like seeing with a beautiful focus on what it around us at any given time. His writing has an influence on my thoughts but I don't know that it has changed my painting.

TMR: You are Americans, why did you choose life in the Old World, and why Assisi?

A.F. This is a long story. In brief, Lani and I had spent time in Italy before we met each other. We loved Italy for the art and architecture and many aspects of life here. When in 1984 I decided to give up a tenured teaching position at American University in Washington, to have more painting time, that was the first time in my life I could freely choose where I would live. Where we might live. Before then, both of us had lived where our families lived when we were children, then where we did our schooling if that was a new place, and then where we found work. We moved to Italy in 1987 because we wanted to live in Italy. For the art and the for the place. And to give our two sons the experience of living abroad, that had meant so much to both Lani and me in our younger years. It seemed a good decision. We both had galleries representing us and we could move anywhere so long as we could get our painting to the galleries. Total freedom to choose where we might be fed best as painters and where our children could grow up as international citizens and not so easily be influenced by the materialism and competitiveness that we saw all around us in the States.

Assisi is a place we loved. The Basilica of San Francesco in Assisi is possibly the most wonderful church in Italy.

TMR: What are the differences between European and American art today?

A.F. I don't keep up that well with contemporary art anywhere. But I don't think that in our times there is a real difference between American and European art. The artist today can be influenced by art from any country and any time. Artists can travel. Books and now the internet allow any of us to see art from anywhere. Both American and European art museums have large and important exhibitions that bring in works from far lands. We are basically exposed to very similar influences no matter where we live if we can get to those museum shows and can find good libraries or collect art books.

TMR: Thank you, Mr. Feltus.

https://www.themontrealreview.com/2009/Alan-Feltus.php