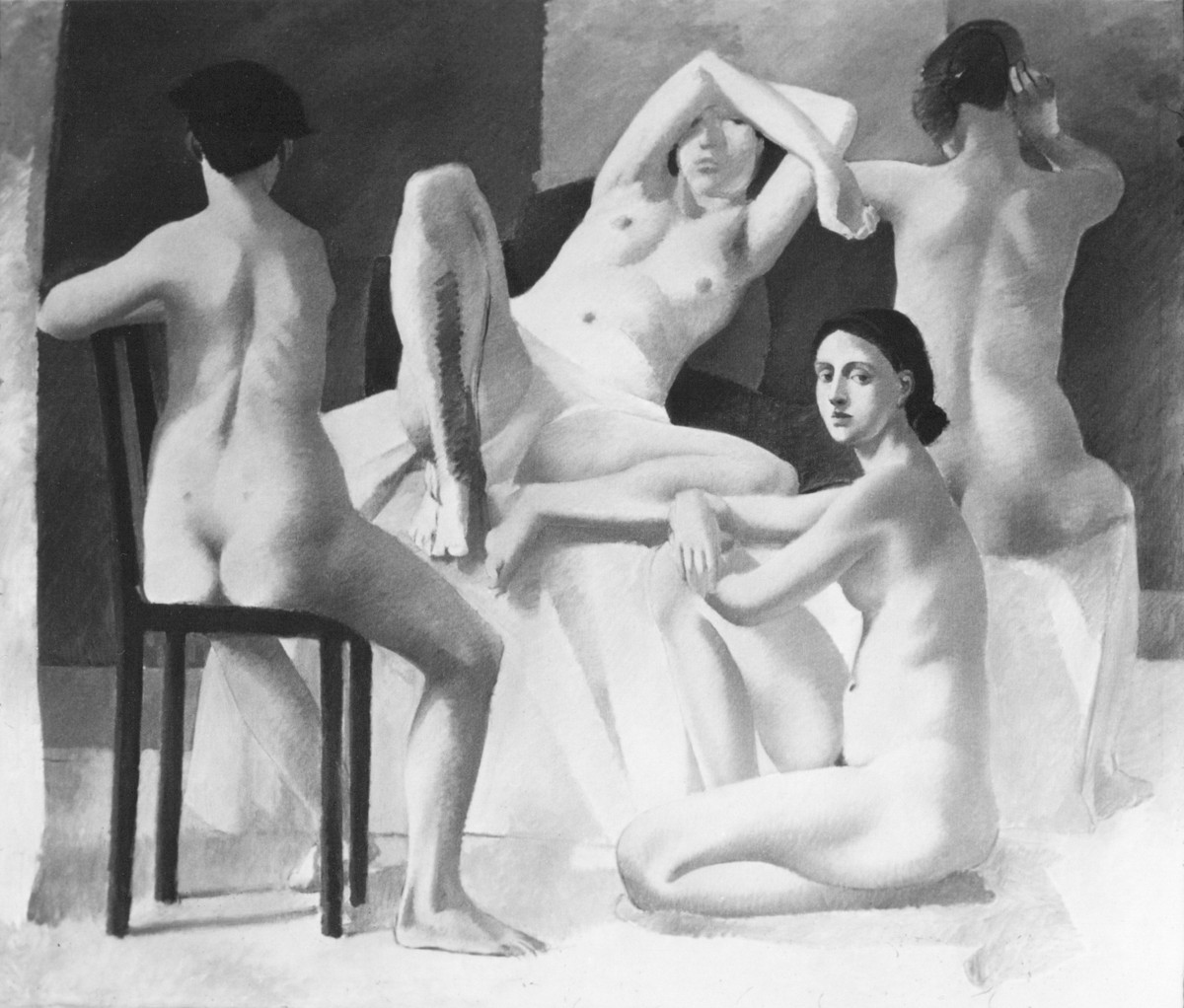

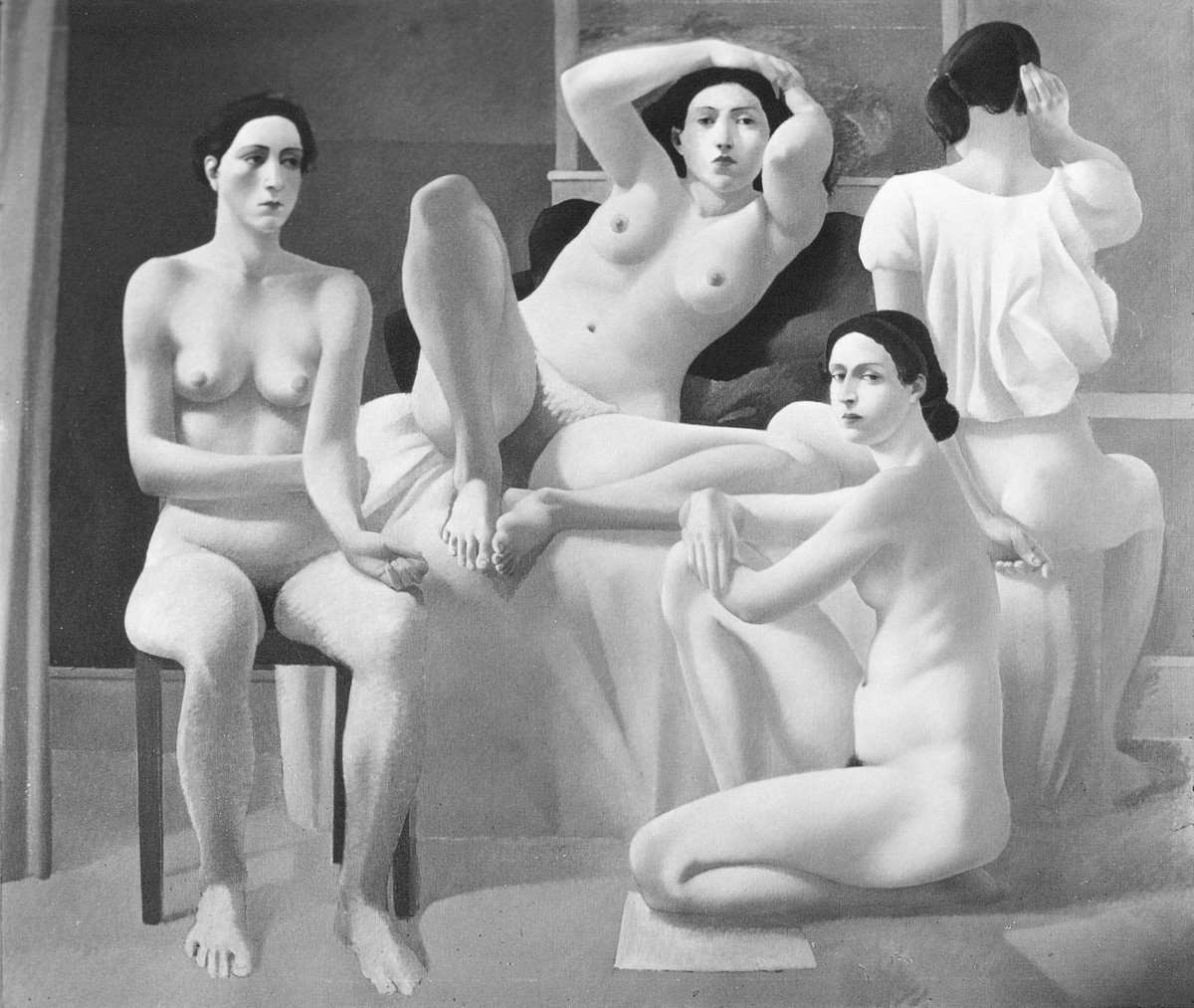

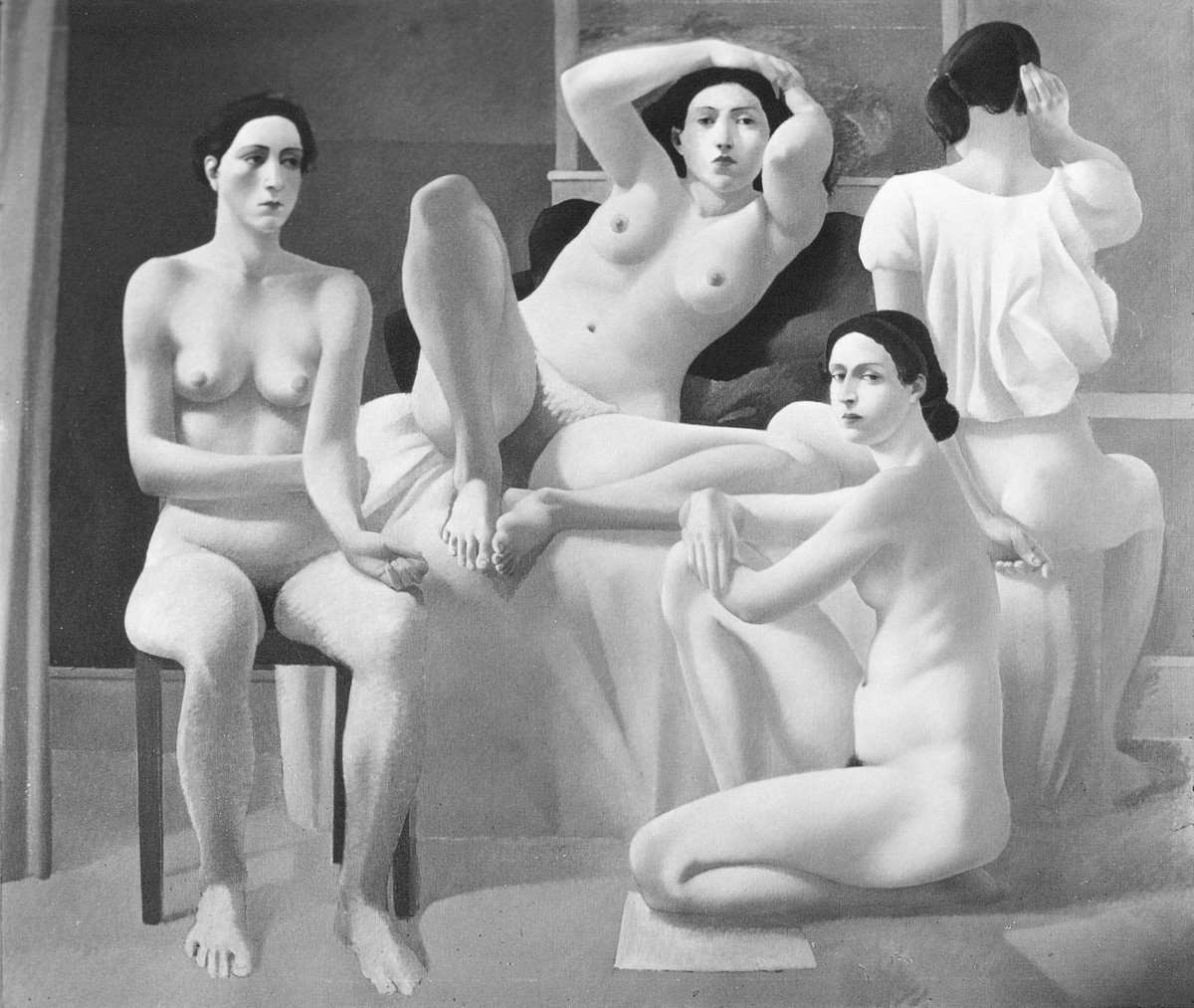

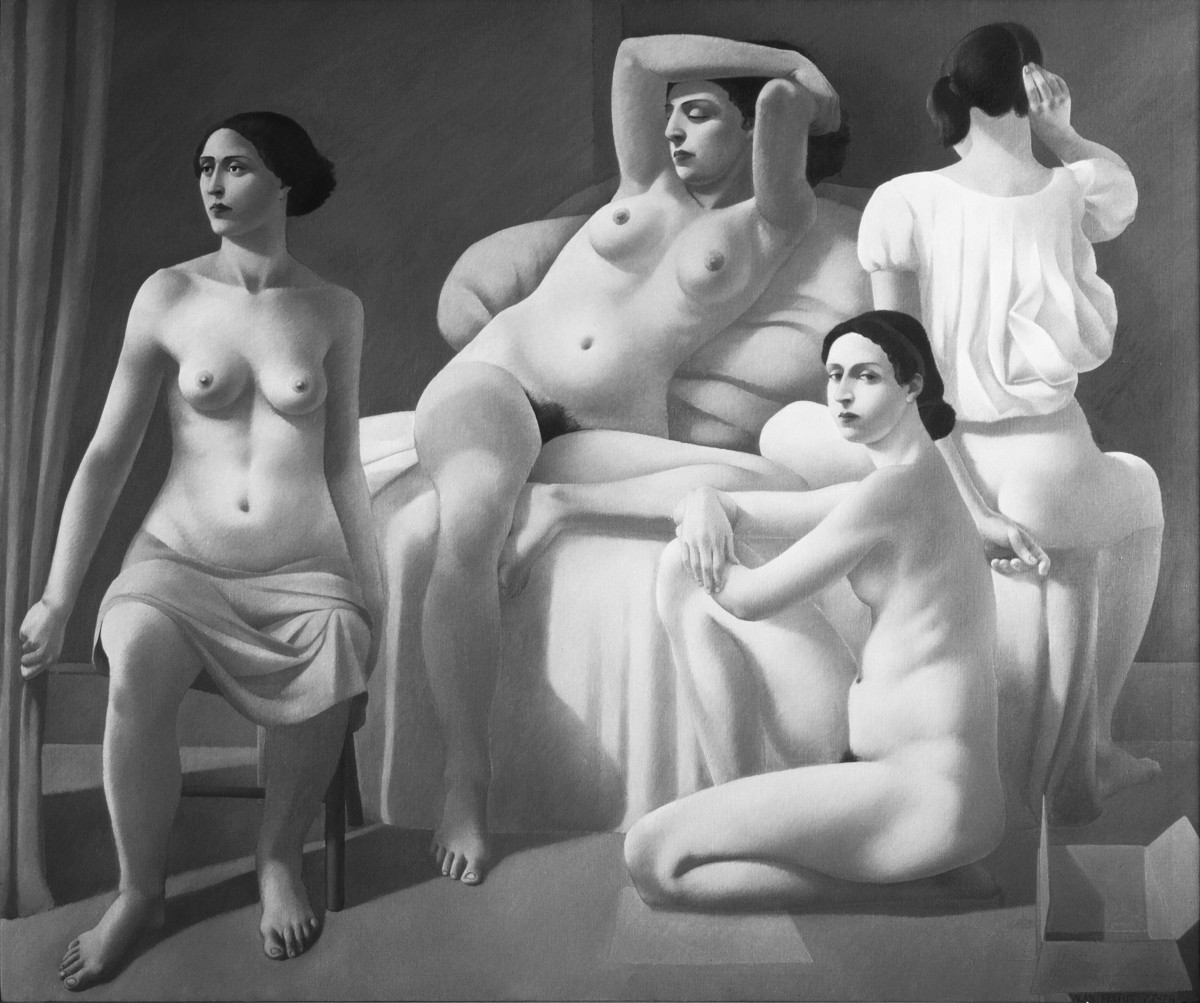

Four Women, 1978, oil on linen, 59 x 69 inches (150 x 175 cm)

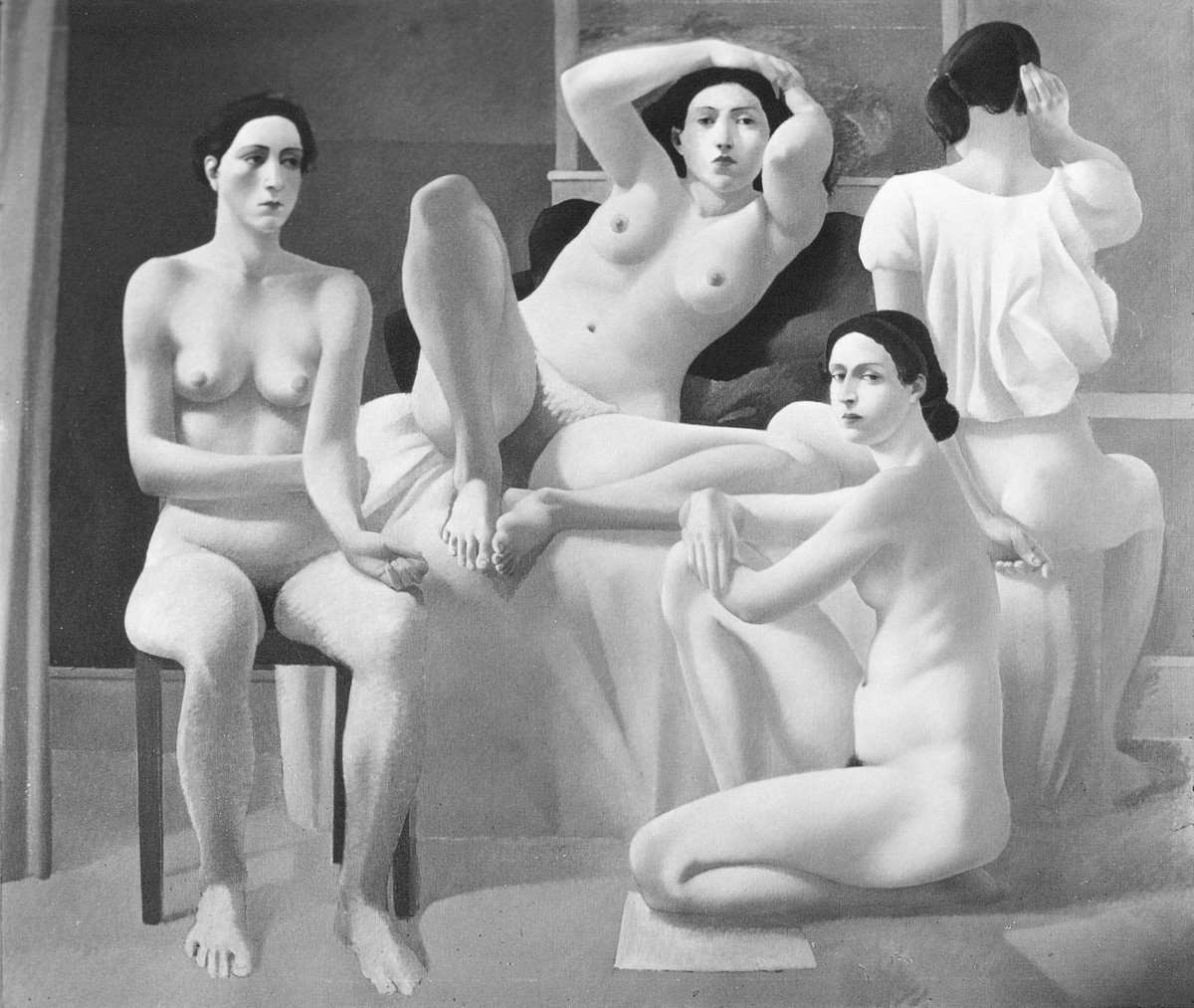

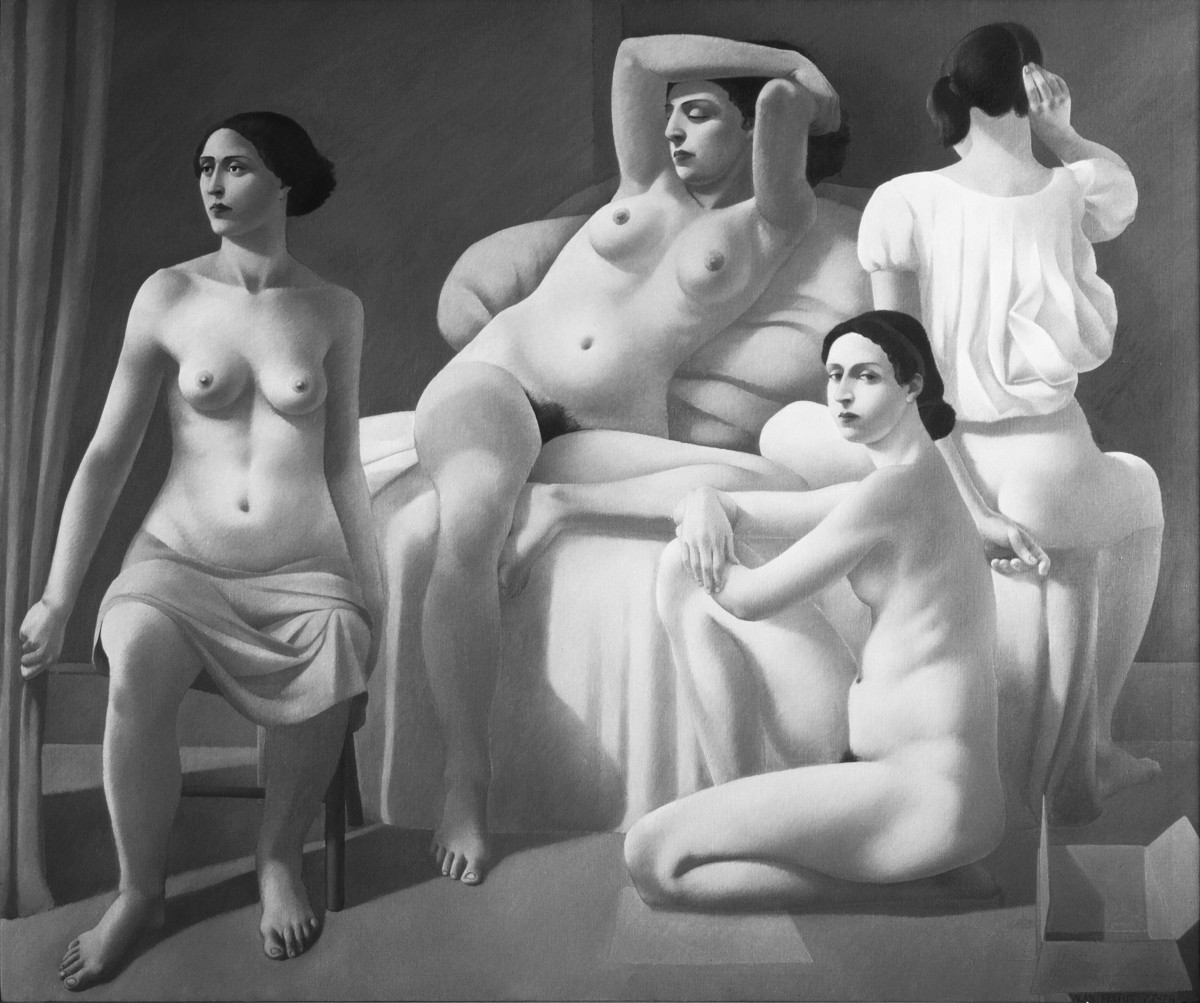

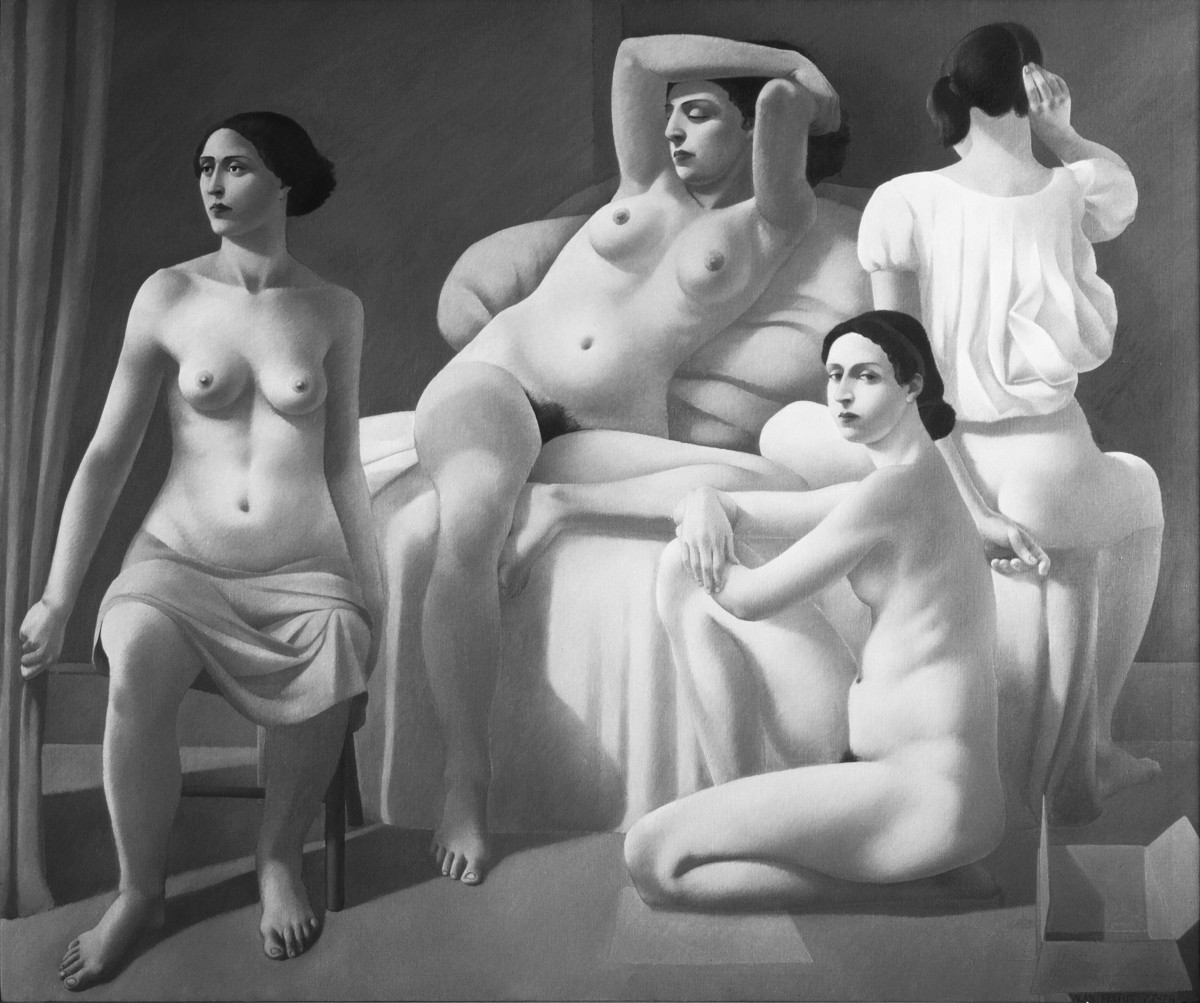

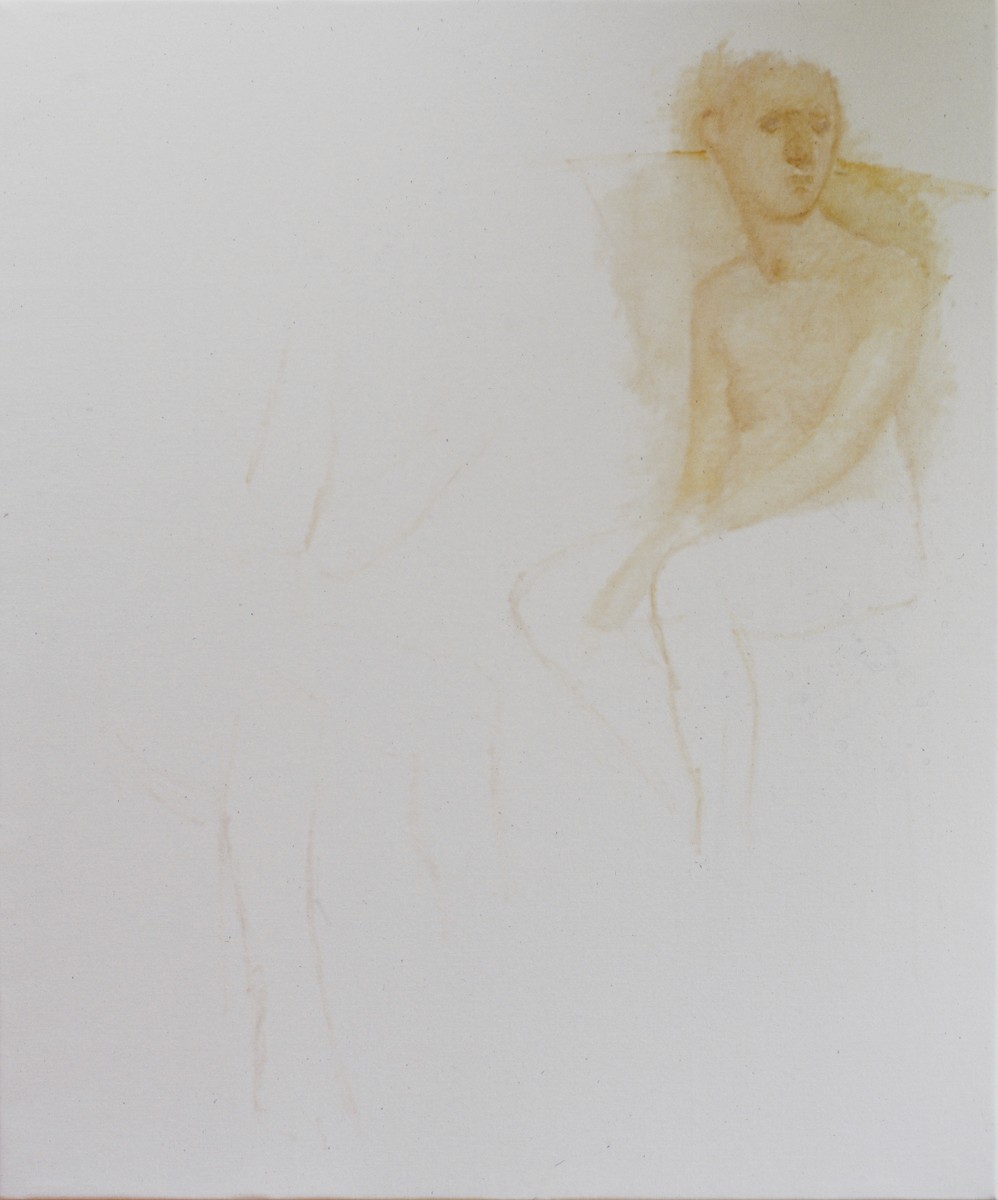

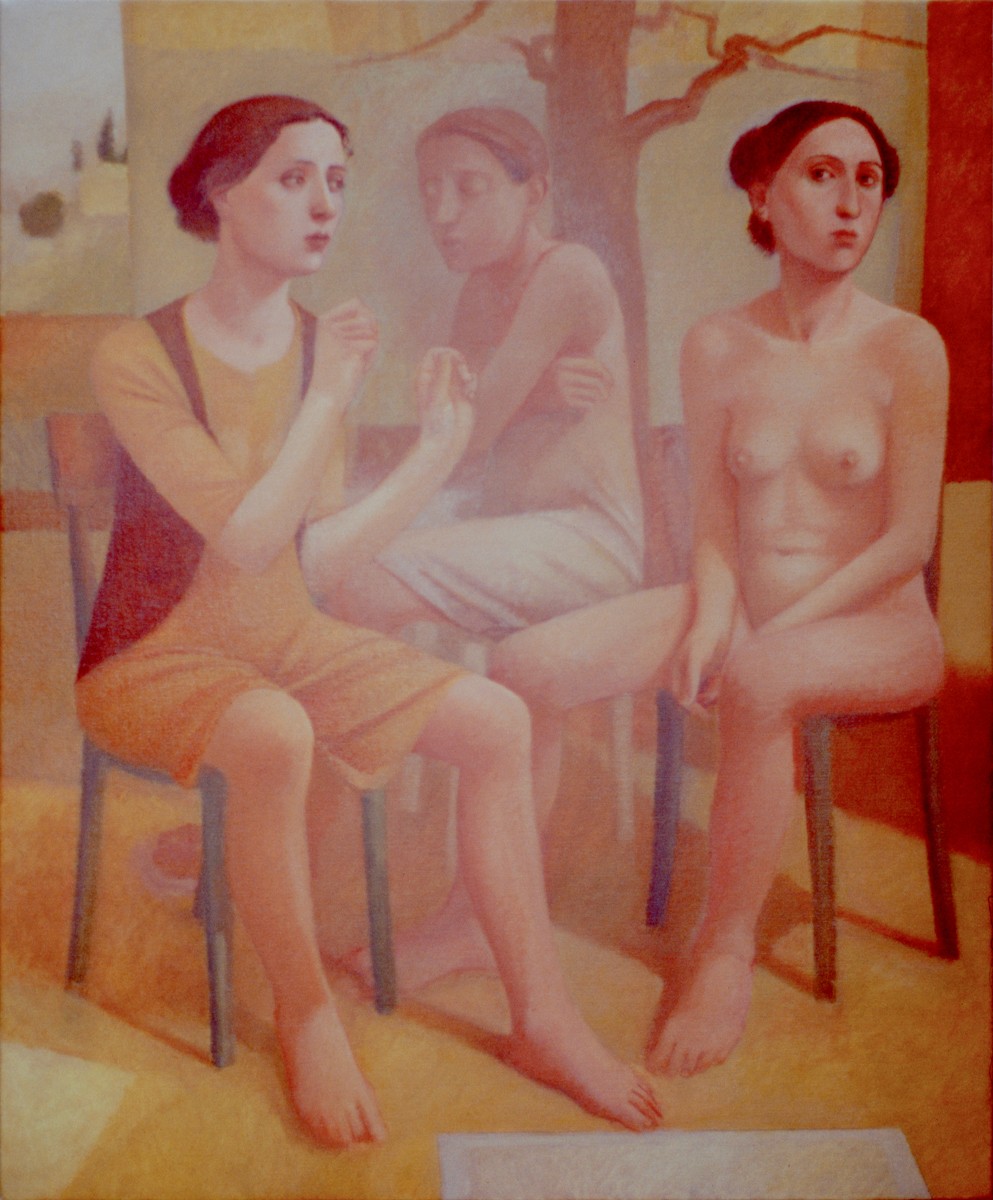

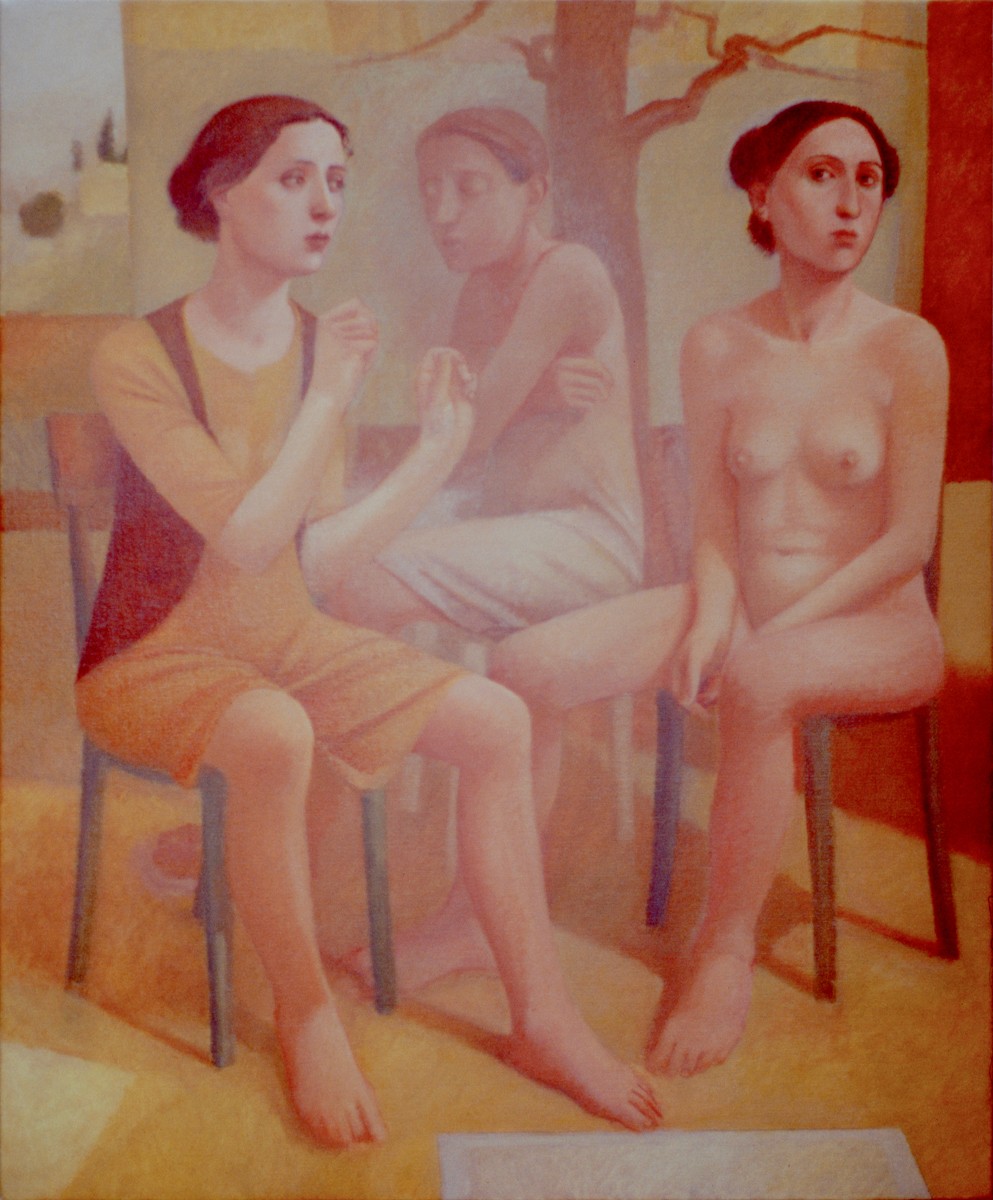

Three Women with Pear, 1981-'82, oil on linen, 70 x 48 inches (178 x 122 cm)

Collection of the American University Museum at the Katzen Arts Center, Washington, D.C.

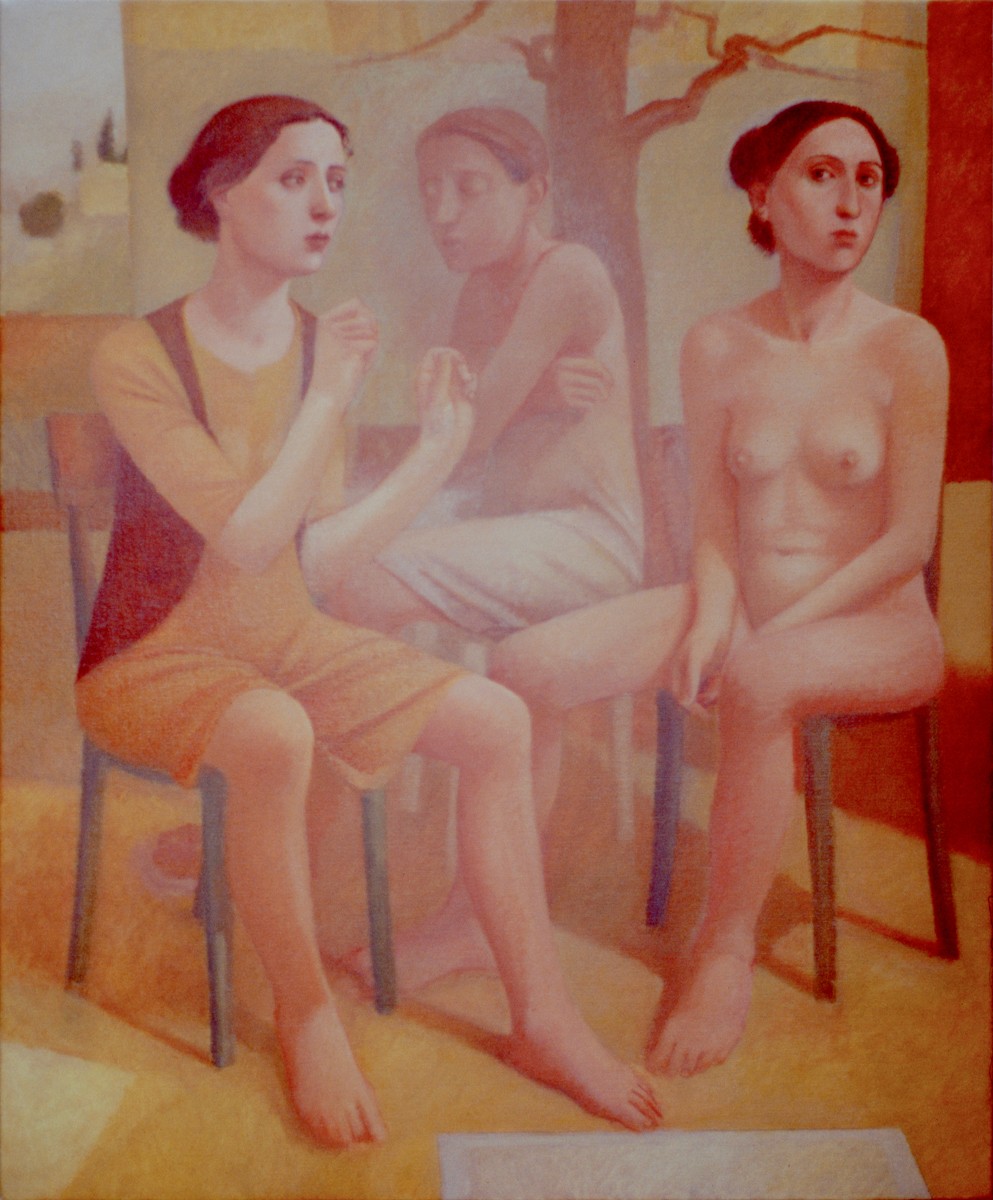

Inner Voices, 2006, oil on linen, 47 ¼ x 39 ¼ inches (120 x 100 cm)

[…] When making a painting, I am choreographing figures and objects. Every element is a considered part of the composition, so any line or color, any object or any space between objects, has been positioned, and then adjusted and adjusted again, and again, to work in a precise way with everything else. This holds true for the division between floor and wall, the shape of a cast shadow, the presence of a book or a teacup, and so on. If I paint a piece of drapery or a piece of paper on a chair, that will be there partly because it has a compositional purpose. It might serve to continue a visual line across the painting’s surface, establishing a relationship between those several parts that line up in a particular way. A piece of paper painted in perspective becomes a tipped plane. Placed on the floor, such a shape can hold an otherwise ambiguous area of color down as a floor and thus define the space. We can create a whole complicated patterned floor drawn in perspective, or we can paint, in effect, one square of that checkered floor that will serve the same purpose.

[…] Typically when I start a new painting, I’ll tentatively place first one figure, and then a second figure on a blank canvas. As I’m shifting them in position to work together, I might add a third. Or I might take out a figure that had been there. A head turns, eyes shift in the direction of their gaze, an arm changes its position. A book or a cup on a table will move. The table moves. A nude gets dressed or a dressed figure sheds her clothing. A chair turns to face the other direction. A wall moves back and a shadow divides it diagonally. Its color changes. A window becomes a landscape painting, or it is painted out. And it goes on like that. Decision making will continue until I accept the way everything is working. This can take weeks or months, depending on the size of the canvas.

From Motherself: an Artist's Memoir, 2024

[…] When making a painting, I am choreographing figures and objects. Every element is a considered part of the composition, so any line or color, any object or any space between objects, has been positioned, and then adjusted and adjusted again, and again, to work in a precise way with everything else. This holds true for the division between floor and wall, the shape of a cast shadow, the presence of a book or a teacup, and so on. If I paint a piece of drapery or a piece of paper on a chair, that will be there partly because it has a compositional purpose. It might serve to continue a visual line across the painting’s surface, establishing a relationship between those several parts that line up in a particular way. A piece of paper painted in perspective becomes a tipped plane. Placed on the floor, such a shape can hold an otherwise ambiguous area of color down as a floor and thus define the space. We can create a whole complicated patterned floor drawn in perspective, or we can paint, in effect, one square of that checkered floor that will serve the same purpose.

[…] Typically when I start a new painting, I’ll tentatively place first one figure, and then a second figure on a blank canvas. As I’m shifting them in position to work together, I might add a third. Or I might take out a figure that had been there. A head turns, eyes shift in the direction of their gaze, an arm changes its position. A book or a cup on a table will move. The table moves. A nude gets dressed or a dressed figure sheds her clothing. A chair turns to face the other direction. A wall moves back and a shadow divides it diagonally. Its color changes. A window becomes a landscape painting, or it is painted out. And it goes on like that. Decision making will continue until I accept the way everything is working. This can take weeks or months, depending on the size of the canvas.

From Motherself: an Artist's Memoir, 2024

© 2024 Alan E. Feltus

ALAN FELTUS is represented by FORUM GALLERY

475 Park Avenue at 57th Street, New York, NY 10022

Email: gallery@forumgallery.com

Tel: +1 (212) 355-4545

SITE MAP:

PAINTING: 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s |

| 2000s | 2010s | 2020s | Small Paintings | Self-Portraits |

© 2024 Alan E. Feltus

ALAN FELTUS is represented by FORUM GALLERY

475 Park Avenue at 57th Street, New York, NY 10022

Email: gallery@forumgallery.com

Tel: +1 (212) 355-4545

SITE MAP:

PAINTING: 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s |

| 2000s | 2010s | 2020s | Small Paintings | Self-Portraits |

© 2024 Alan E. Feltus

ALAN FELTUS is represented by FORUM GALLERY

475 Park Avenue at 57th Street, New York, NY 10022

Email: gallery@forumgallery.com

Tel: +1 (212) 355-4545

SITE MAP:

PAINTING: 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s |

| 2000s | 2010s | 2020s | Small Paintings | Self-Portraits |